2017 Brands of the Year: 5 Impact Areas

In its 11th annual feature, Pharm Exec breaks a bit from the norm, to instead profile five products that are shining the spotlight on five critical and highly debated aspects of healthcare and R&D at the moment.

For Pharm Exec’s 11th annual Brand of the Year feature, we decided to try something different and change our approach. This year, instead of picking one hot or established product to highlight, we are profiling five brands that are synonymous at the moment with five critical and “brand impact” topics in healthcare and R&D. Selected with the input of our Editorial Advisory Board, these are the products driving much discussion and debate-or are good case studies-in their respective categories. After all, the stories surrounding biopharma brands aren’t just about the sales or the science. Some are lightning rods for the bigger issues affecting public health and drug access. Others represent potential success stories for new care models, or hopeful game-changers in addressing high-risk chronic disease and the life-robbing symptoms of mental illness.

Pharm Exec’s five Brands of the Year are profiled ahead. For a look back at each of the first 10 winners and where they stand today, check out our retrospective here.

Brand Impact: Pricing/Reimbursement

EpiPen

A lesson in trust

This year, we didn’t just pick the shining brand stars for our choices to highlight. Rather, we went for “impact” in different commercial areas. Who could argue that Mylan’s challenges with pricing and reimbursement for EpiPen didn’t have an impact on the pharma industry in 2016?

What began as a pricing issue became a lesson for industry executives. And not only our industry executives, as an article from Hospital & Health Networks highlighted in September. Says author and consultant Paul Keckley, “Mylan is a case study worth review by every organization in healthcare. Trust is invaluable in healthcare. It cannot be compromised, and when it is, boards must be attentive and leaders responsive and credible.”

While Mylan CEO Heather Bresch has not been ousted for the scandal that erupted last August, she has had plenty to say about the supply chain, which she-as one person characterized to Pharm Exec-threw under the bus. In a January interview with CNBC, Bresch blamed the complex pharmaceutical distribution system, from which all profit from selling drugs.

It is true that market access for a drug is not easy-ask any C-suite executive. Patient access is fraught with tiered co-pays, Medicare, prior authorizations, stepped therapy, generics, coupons, rebates…not to mention what Bresch noted in her interview, high-deductible insurance plans. In order to make sure that patients have

access to their drugs, pharma must engage with pricing plans, operations and implementations with the members of the supply chain-health plans, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmacies.

To the high-deductible health plans (HDHP), 29% of Americans are currently enrolled in employer-sponsored HDHPs, up from 4% in 2006. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Education Trust, Employer Health Benefits Annual Survey 2016, the average family contribution in a HDHP is $4,280. As noted, the high-deductible plans are becoming more popular with employer-sponsored offerings and lead people to pay more for a medication in the first few months of a year, until they reach their deductible and then prices come down. Physicians don’t understand what their patients are going to be charged based on whichever plan they are in-and pharma is now spending time and energy educating and helping physicians understand their individual patient’s pricing. There’s also the realization among biopharma companies that they are having a hard time adjusting their forecasts and programs due to this “seasonality” of access. In a recent discussion, experts explained that to manage those patient payment problems and access issues, companies are trying to time their coupons and rebates for those high-yield months.

This is not to say that Bresch be given a pass for the complex supply chain. EpiPen is generic, comes in a two-pack and the drug is only stable for one year. So every year, schools, hospitals, parents and others need to have non-expired EpiPen on hand. Raising the price in advance of another purchase cycle may be good business for the shareholders. But it’s not good business for trust. “Just because you can raise the price, doesn’t mean you should,” one executive told me. “That decision and its impact to your reputation needs to be carefully weighed.”

In early September, Brent Saunders, CEO of Allergan, set out the social contract to patients that Allergan would follow, and it did discuss price. Other biopharma executives from AbbVie, NovoNordisk, Valeant and Takeda followed with varying forms of pricing commitments. Others, including Regeneron and Mylan, said 10% limits weren’t the answer to the supply chain problem. Still others believe pharma is stepping it up so it won’t be regulated by the government.

In the meantime, Mylan’s share price is bouncing back since the scandal-it was 37.89, as of press time. And there is speculation that Mylan could be an acquisition target, with some reports saying Pfizer was considering. In mid-December, Mylan launched its generic to EpiPen Auto-Injector, which has the same drug formulation and device functionality as the branded product.

Mylan’s choice to raise the prices of EpiPen since 2006 have given a great deal of fodder for the public, government, and stakeholders in the drug supply chain to think about. Ex-GSK CEO Andrew Witty changed the company’s portfolio strategy because he believed that increasing prices is not sustainable and volume would win the day. There is definitely more to come on the pricing and market access issues in pharma.

- Lisa Henderson

Brand Impact: Clinical Efficacy

Jardiance

Diabetes game-changer

As Pharm Exec Editorial Advisor Cliff Kalb observes, the concept of offering patients a means to control adult-onset diabetes and reduce cardiovascular (CV) mortality has been a goal of many pharma companies for several decades. “It became apparent to the key opinion leaders (KOLs) in endocrinology and cardiovascular disease that documented evidence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and/or obesity were all contributing CV risk factors that could lead to early death,” he explains.

Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and Eli Lilly’s Jardiance (empagliflozin) was first approved by FDA in 2014 as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve blood glucose levels in adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D); in its supplemental new drug applications, BI/Lilly sought a new indication that Jardiance also decreased the incidence of CV death and the risk of death or hospitalization for heart failure in patients with T2D. The team at BI and Lilly would be the first to prove to the satisfaction of FDA that a reduction of these risks could be shown in large numbers of patients with one drug.

Results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of over 7,000 adults with T2D and an established history of heart disease showed that Jardiance led to a 38% reduction in risk of heart-related death and a 32% reduction in overall death. In December, FDA approved the new indication for Jardiance to reduce the risk of CV death in adults with T2D and CV disease. Kalb calls BI/Lilly’s efforts “a classical case history of the perseverance of pharma in a Phase IV trial to provide real value to patients of life-extending benefits.”

Graham Goodrich, BI’s vice president of diabetes marketing, told Pharm Exec that he sees Jardiance in the context of past landmark trials in the CV space that have “fundamentally changed the practice of medicine,” such as HOPE (for the ACE inhibitor ramipril) and the 4S trials for simvastatin. He explains: “Any time there has been a major paradigm shift in medicine, three things exist: a dramatic unmet need; a huge financial burden on the healthcare system; and a disruptive innovation, which forces action when the data is truly understood. All these three factors are present in the case of Jardiance.”

Effecting a paradigm shift, of course, takes time. “Given that two-thirds of all patients with type 2 diabetes will die from CV disease, there’s an urgency to educate and engage the marketplace about the intersection between type 2 diabetes and elevated cardiovascular risk. We’re broadening the conversation from only a glucose management discussion to one that elevates the importance of CV risk reduction,” says Goodrich.

“And what we’ve seen is that knowledge is power. When people understand the facts, costs and the data driving Jardiance, they’re compelled to act. Hopefully, that then leads to accelerating that behavior change and ultimately saving lives.”

Sales of Jardiance reached $460 million last year, but this, as EP Vantage noted last month, was before taking its new CV label into account. Since the new indication approval went public, “the response has been impressive,” says Goodrich. “Within the first four weeks of promotion, we became the NBRx share market leader. We’re number one in terms of new starts with cardiology, endocrinology and we’re about to eclipse the number one in primary care.”

The industry press has suggested that Jardiance’s rise could be slowed in the event of positive CV outcomes data for other SGLT2 inhibitor drugs, such as J&J’s Invokana and AstraZeneca’s Farxiga. But Goodrich welcomes the publication of other data. “Patients and clinicians need alternatives,” he says. “What we’ve seen in other categories of diabetes is that these molecules tend to be different, not just from a molecular standpoint but also in terms of differences within class. The more data we have available for clinicians to analyze, the more we will be able to understand those differences and apply them appropriately to patients.”

BI/Lilly is now running two outcome trials investigating Jardiance for the treatment of people, both with and without T2D, with chronic heart failure. “We see a long runway,” says Goodrich. “In the non-diabetes population, about half of all people who develop heart failure die within five years of diagnosis. There is optimism that Jardiance can extend into this population.” While he is not able at this point to elaborate on the progress of the new trials, Goodrich says that, so far, there are “certainly positive signals that suggest there could be a benefit for what remains a huge unmet need.”

- Julian Upton

Brand Impact: Social Policy

Narcan

Potent life-saver, vicious circle

“It literally brings back the dead."

With that explanation of support for why Pharm Exec should choose Narcan as a Brand of the Year, who could say no? For emergency use with people suspected of a heroin or opiate overdose, Narcan injectors work within five minutes.

Albert I. Wertheimer, professor and director, pharmaceutical health services research at Temple University and member of the Pharm Exec Editorial Advisory Board, said, “Narcan is one of those products that comes along ever so rarely. There are many drugs, some simple and others complex, for acute and chronic diseases, but most of those have alternatives or at least other choices available to the prescriber. For example, there are eight or nine statins, a dozen ACE inhibitors, but there is only one Narcan.”

Naloxone, the chemical name for Narcan, is a mu-opioid antagonist that was first introduced to the market in 1971 to prevent patients from overdosing on pain medication during and after surgeries in hospitals. It has no-known adverse events and is efficacious.

There are other brand names for naloxone, but like epinephrine, it is known more by its brand name. Narcan’s manufacturer, Adapt Pharma, received FDA approval for its 2mg nasal spray at the end of January. The 4mg spray was granted in February 2016 and both dosages are labeled to show response in a patient within two to three minutes. The 4mg dose was fast-tracked and given priority review because the nasal spray delivery was viewed as much easier to administer in emergency situations. The FDA noted in its press release: “In clinical trials conducted to support the approval of Narcan nasal spray, administering the drug in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection, and achieved these levels in approximately the same time frame.”

Prior to the FDA approval of the nasal spray, first responders did use a liquid form of naloxone via an atomizer to spray into victim’s nostrils, because that delivery eliminates the use of needles, de-risking accidental needle sticks.

Wertheimer further noted of Narcan: “It can be administered by a policeman or fireman or school nurse or practically anyone. It works in nearly all cases immediately and became available to tackle a huge epidemic we don’t usually consider as a major epidemic.” In the 1990s, naloxone’s use was expanded as an emergency remedy for addicts overdosing on opiates. And with the current opioid epidemic, Narcan or naloxone distribution programs, which aim to provide not only emergency personnel with the drug, but also laypersons, has increased.

Conflict and concern

As distribution programs have increased, so have concerns that Narcan is an “enabler” to drug use or overuse. In 2014, according to the Marshall Project, the nation’s largest police department, New York City, purchased 20,000 Narcan kits for its officers. However, some law enforcement departments are not on-board with providing Narcan. Some have stated the logistics of transferring Narcan from officer’s vehicles around shift changes is not manageable; shelf-life issues and restocking (Narcan’s shelf-life is 18 to 24 months, should be stored between 59°F to 86°F and kept away from direct sunlight); and an overall concern that they are not medical professionals-though they typically are first responders-and may not be helping the larger drug problem issue.

As stated in the Marshall Project, in Quincy, Mass., a town of 93,000 just south of Boston, police officers have responded to 591 overdoses since they started carrying Narcan in 2010, reversing 418 of them. However, some officers stated that they have “reversed” the same person more than once. And that Narcan doesn’t help people stop being addicts.

In a 2013 article in Drug & Alcohol Dependence, officers were interviewed on their attitudes around overdose response, with these common themes or results: “….feelings of futility and

frustration with their current overdose response options, the lack of accessible local drug treatment, the cycle of addiction, and the pervasiveness of easily accessible prescription opioid medications in their communities. Overdose prevention and response, which for some officers included law enforcement-administered naloxone, were viewed as components of community policing and good police-community relations.”

According to a CDC report on naloxone in 2014 based on 2013 statistics, it found that of 43,982 drug overdose deaths, heroin accounted for 19%, while prescription opioids accounted for 37%. In a flip of statistics, heroin was involved in 81.6% of reported naloxone reversals, while prescription opioids were involved in 14.1%.

While heroin and opioid addiction crosses socioeconomic classes, a 2014 report from the Bureau of Justice Assistance stated certain groups, including veterans, residents of rural and tribal areas, recently released inmates, and people completing drug treatment/detox program are at an especially high risk of opioid overdose.

However, overall, the increases in heroin and opioid addiction are tragic in the US, with the CDC reporting: “the greatest increases have occurred in demographic groups with historically low rates of heroin use: women, the privately insured, and people with higher incomes. In particular, heroin use has more than doubled in the past decade among young adults ages 18 to 25.”

At a recent pharmaceutical compliance conference, the opioid epidemic was discussed and members inside and outside of industry urged action from pharma. Prescription opioids are literally the “gateway” drug to heroin, with many addicts starting with oxycodone or percocet received or taken from someone they know, then onto heroin or fentanyl because it is cheaper and readily available. Prosecutors urged pharma to use data mining to uncover unsafe prescribing habits or zero in on practices that encourage overprescribing, as well as participate in collaborative activities to address the epidemic.

As one panel member noted: “The epidemic is spiraling out of control and it’s going to get worse before it gets better. And the public will look to someone to fix it. And they will say to pharma, ‘you should have done more.’”

- Lisa Henderson

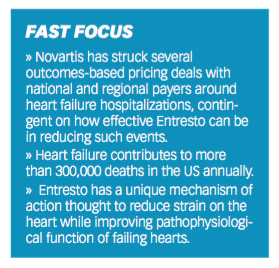

Brand Impact: Value-Based Contracting

Entresto

Performance pacesetter?

It’s no secret healthcare spending in the US has grown greater than the rate of inflation, with experts warning that even if future legislative and other reforms do succeed in curbing costs to a degree, by 2050, healthcare investment could account for 40% to 50% of the nation’s GDP. Most agree such a path is unsustainable-a realization that has shifted current thinking around healthcare from a volume to a value focus, resulting in the emergence of alternative payment models designed to incentivize product value and true innovation in patient care.

One such model, though still very much in the proving-ground stages, is value-based contracting, also referred to as outcomes-based or pay-for-performance pricing. Deals struck under these frameworks, between biopharma manufacturers and health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers, offer potentially promising ways to support patient access to novel medicines while demonstrating the real-world benefits of these drugs. Outcomes of therapy effect are measured from payer databases using pharmacy and medical claims.

Novartis and its heart failure (HF) drug Entresto, approved by the FDA in 2015 as a first-in-class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, are on the forefront of testing the value-based pricing waters. In May 2016, Novartis inked outcomes-based contracts with Aetna and Cinga, and a month later reached a deal with Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. Each payer is provided a discount on Entresto if the drug reduces hospitalizations for commercially insured patients with congestive HF. In exchange, Entresto becomes a preferred drug, subject to prior authorization, on the insurers’ formularies. In the clinical setting, Entresto, in a trial of 8,442 patients, significantly reduced 30-day hospital readmissions compared to traditional treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril. In November, a new analysis on HF readmissions from the study revealed that Entresto reduced the risk of both first and subsequent events of repeat HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular deaths following HF hospitalization-compared to enalapril.

A twice-a-day tablet, Entresto was approved in Europe in late 2015. The drug consists of acubitril, a new molecular entity, and the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) valsartan.

“Entresto is a good candidate for outcomes-based contracts because there is a measurable outcome and data to evaluate is accessible,” Eric Althoff, Novartis’s head of global media relations, told Pharm Exec. “By collaborating with payers on solutions-oriented approaches to reimbursement, we believe we are doing our part to help shift the paradigm of pricing in our healthcare system."

An analysis published last June in JAMA Cardiology found that timely and broad adoption of Entresto by all eligible HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) could prevent or postpone more than 28,000 deaths each year in the US. Novartis, last year, established the FortiHFy clinical program, which it said will include studies designed to collect data on symptom reduction, efficacy, quality-of-life benefits and real-world evidence with Entresto. US guidelines now recommend the drug as standard of care for HFrEF and alternative to ACE inhibitors and ARBs, and urge physicians to switch patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms to Entresto. Updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology also recommend Entresto in patients fitting the profile.

Strong data and endorsements aside, Entresto’s promise in generating value for patients and the healthcare system will come down to how well it manages the high-risk HF patients intended to benefit the most, experts believe. Specific terms of Novartis’s value-based contracts and the outcomes tracked are confidential.

“If any of these are going to work, Entresto would be the one,” says Shiraz Hasan, vice president, life science strategy, Capgemini Consulting, referring to the spate of recently announced industry value-based pricing deals. “It definitely will reduce cost to the overall healthcare system, if it’s used by the right patients.”

The biggest hurdle for Entresto may be convincing cardiologists, used to prescribing cheaper and often effective generics, to change their prescribing habits. While Entresto’s price tag of $4,500 a year isn’t near the realm of other highly touted drug entries in recent years, the cost could still present a strain for some patients. Hasan notes as well that physicians are reluctant to stray from established, clinical-driven treatment guidelines, concerned that any unfavorable outcome will significantly cut their reimbursement.

That mindset, however, is changing in some circles, Hasan says. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospitals, for example, has looked closely at ways to leverage real-world evidence among high-risk patient groups in treatment protocol and guideline decisions. In Entresto’s case, the key will be monitoring such subsets of HF patients who take the drug to determine if reduced hospitalizations are indeed a result of the treatment and not other factors. Hasan notes that the findings could help increase Entresto’s use in broader populations, too, where the healthcare costs and savings could be spread around.

Entresto's slow sales uptake since its launch has been attributed to the drug's large proportion of Medicare Part D patients-reportedly 65% of its target reach-where, due to the mechanics in the system, it can typically take between six and 18 months for those patients to get access. Entresto is positioned for a significant revenue jump in the next couple years. According to a report from Market Realist, Novartis expects Entresto to reach sales of more than $500 million in 2017, due to improving access for Medicare and the commercially covered patient population, the latter boosted by the company’s value-based contracting arrangements.

"We are committed to continuing our work with customers to identify new approaches that can help improve patient outcomes," says Althoff. "We hope the important progress payers have helped us make on this front will encourage others in the industry to embrace and employ value-based pricing models."

Despite the attention, the jury is out on just how beneficial these deals will be for patients and healthcare stakeholders. A host of challenges remain, from payers having the appropriate staffing and resources in place to manage very complex datasets and analysis, to concerns over data sharing and trust, and the potential of rebates and claims validation, traditionally processed quarterly, falling outside of payment windows due to the time needed to collect quality measures on outcomes.

“The drug is only one piece of the equation,” Hasan told Pharm Exec. “It also has to do with care coordination, doing what’s right for the patients. Investing in it so that the systems that address the physicians and the coordination-their electronic records, how they think about their patients-and provide the best quality of care are bigger factors than the drug itself. … The industry is starting to think about those things, because that’s really what’s ‘beyond the pill.’”

- Michael Christel

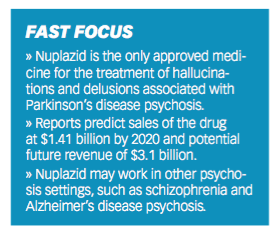

Brand Impact: First-in-Class

Nuplazid

A little peace of mind

An estimated 40% of the US’s one million Parkinson’s disease patients suffer Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), a condition characterized by sometimes severe hallucinations and delusions. As well as further debilitating the Parkinson’s disease patient, PDP leads to significant caregiver burden-with patients 2.5 times more likely to be placed in long-term care than PD patients without hallucinations-and is linked to higher mortality.

Illustration for Nuplzid depicts a montage of hallucinations on side of the brain and normal brain on the other.

Acadia Pharmaceuticals’ Nuplazid (pimavanserin), a selective serotonin inverse agonist (SSIA), is a first-in-class antipsychotic that functions as an inverse agonist and antagonist, blocking agonists and inhibiting basal signaling. It has selective affinity; its strongest affinity is for the 5-HT2A receptor and it has lesser affinity for the 5-HT2C receptor. In vitro, Nuplazid has no appreciable affinity to dopaminergic, histaminergic, adrenergic, or muscarinic receptors, but its precise mechanism of action is unknown.

Results from a Phase III trial of 199 PDP patients showed a 37% improvement in patients taking Nuplazid (compared with 14% with placebo) in the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms adapted for Parkinson’s disease (SAPS-PD), a modified version of SAPS that included the domains most reflective of the prevalence and severity of hallucinations in PDP. Based on these results, Nuplazid won FDA approval in April 2016 and is currently the only approved medication for the treatment of hallucinations and delusions associated with PDP.

In its “7 New Blockbuster Drugs to Watch in 2016,” Fortune predicted sales of Nuplazid at $1.41 billion by 2020. The report noted that the Phase III trial had shown that the drug, in targeting only the 5-HT2A receptor, does not worsen motor symptoms “while improving night-time sleep, daytime wakefulness, and caregiver burden.” Fortune added that Nuplazid may also work in other psychosis settings, such as

schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease psychosis (ADP), leading to “a potentially massive and, therefore, lucrative market.”

Michael Kramer, in a June 2016 Seeking Alpha article, agreed that the opportunities for Nuplazid are large. He added: “My estimate is for Acadia to capture about 130,000 patients, which could put potential revenue at $3.1 billion.” He later noted, however, that the “most critical event will be an update on the company’s Phase II trial in ADP." Acadia went on to report success in a mid-stage study targeting Nuplazid in 181 ADP patients in December 2016. Using the NPI-NH (Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home) Psychosis score, investigators tracked a 3.76-point improvement in psychosis at week six, compared to a 1.93-point improvement for placebo. But John Carroll of Endpoints News emphasized in December that “one big problem” was that the drug failed to hit an important milestone on the psychosis score at week 12, where it maintained the improvement seen at the week 6 primary endpoint but did not statistically separate from placebo.

Nevertheless, Bret Jensen observed on March 3 in Seeking Alpha that Acadia had “surged ahead some 80% over the past year” and that “initial sales rollout has exceeded expectations,” with Nuplazid already seeing some off-label use outside of its approved indication. He noted that there appeared to be “a nice increase in repeat subscribers,” as well as good reimbursement network expansion as Nuplazid gets into more Medicare formularies. Jensen concluded that the most likely scenario for Acadia is that it will be purchased “by a larger player at a higher price sometime in 2017.”

Amid mounting speculation around Acadia, it is worth noting the experience of one of the first patients to take Nuplazid. A March article by Mosaic Science on The Caregiver Space website recounts the tale of Ruth Ketcham, a PDP sufferer who took part in the Phase III trial of pimavanserin five years ago. Ruth’s vivid and disturbing hallucinations had begun one year after her diagnosis with Parkinson’s. Within weeks of taking the drug, recalled her daughter, Ruth’s hallucinations had drastically reduced, and while there were still some mild symptoms, they were “nothing like before.”

Her family could not confirm, of course, whether Ruth had received Nuplazid or a placebo at the trial, but her daughter was convinced she had received “the real drug.” In March of this year, Ruth, 93, was still taking the treatment and the results had been “dramatic for the whole family,” according to the Mosaic Science peice. Her daughter explained: “I ask my mother: ‘What does this mean to you? … And she says: ‘It gave me a normal life back.’ Five years later I still cry talking about it. It gave us years with my mother that we wouldn’t have had.”

- Julian Upton

Addressing Disparities in Psoriasis Trials: Takeda's Strategies for Inclusivity in Clinical Research

April 14th 2025LaShell Robinson, Head of Global Feasibility and Trial Equity at Takeda, speaks about the company's strategies to engage patients in underrepresented populations in its phase III psoriasis trials.

The Misinformation Maze: Navigating Public Health in the Digital Age

March 11th 2025Jennifer Butler, chief commercial officer of Pleio, discusses misinformation's threat to public health, where patients are turning for trustworthy health information, the industry's pivot to peer-to-patient strategies to educate patients, and more.

Bristol Myers Squibb’s Cobenfy Falls Short in Phase III Trial as Add On Therapy for Schizophrenia

April 23rd 2025In the Phase III ARISE trial, Cobenfy administered as an adjunctive treatment to atypical antipsychotics for patients with inadequately controlled schizophrenia did not achieve statistically significant improvements.