Crackdown on the C-Suite

Pharmaceutical Executive

Lewis Morris, top lawyer in HHS's office of inspector general, explains his new move to target pharma execs for serious and ongoing healthcare fraud.

Over the past decade, the drug industry has paid tens of billions of dollars to settle state and federal lawsuits involving the False Claims Act—which covers defrauding Medicare and Medicaid, promoting drugs for unapproved uses, paying kickbacks to doctors and pharmacies, and the like. Most of the top 100 pharmas have been nailed at one time or another. The Justice Department is currently investigating nearly 200 pharma fraud cases involving more than 500 drugs. In 2009 alone, 16 cases were settled, netting Uncle Sam more than $4 billion.

Yet while industry leaders like Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Lilly have paid some of the biggest settlements, they are also some of the worst recidivists—evidence that the current system is failing. Major drugmakers now set aside hundreds of millions of dollars to settle False Claims Act charges, and contrary to official statements of contrition, these reserves are viewed as merely the cost of doing business.

Still, record-breaking settlements make the news, attracting the notice of Congress and regulators. Stories about off-label promotion of drugs with serious adverse effects to children, the elderly, prisoners, and the mentally ill have sparked a demand for justice. Now the Obama administration has announced a new enforcement strategy that will take full advantage of the False Claims Act's provisions. Offending drugmakers will increasingly be forced to relinquish product exclusivity. More stunning, the executives under whose watch serious violations occur will be banned from doing business with the government—effectively booting them out of the industry.

Sound harsh? Lewis Morris, a 29-year veteran of the Office of the Inspector General at HHS—and its top lawyer—was more than happy to make the "responsible corporate official" case to Pharm Exec. —Walter Armstrong

Pharm Exec: Can you begin by explaining what you do as the counsel to the Office of the Inspector General?

Lewis Morris: Over the last decade, the Department of Justice and the Inspector General's Office have been pursuing a significant number of cases involving the pharmaceutical industry, as well as device manufacturers, hospitals, and doctors. Under the civil False Claims Act, a company can be liable for promoting the off-label use of a drug, for misrepresenting the pricing of a drug to Medicaid or Medicare, or for other fraudulent conduct. In addition, a pharmaceutical manufacturer can be liable under our criminal authority for submission of fraudulent claims, paying kickbacks to doctors, or other activities. After a case has been thoroughly investigated by our agents and partners in law enforcement, the question becomes how to structure a global settlement that puts the matter to rest in the best interests of the American people. That's where our Office of Counsel comes in.

The OIG has a unique authority to exclude from Medicare and Medicaid any individual or entity that has been convicted of healthcare fraud, abuse, or related offenses. If a company has engaged in, say, a $100 million fraud—that's a pretty modest sum these days—we have to make a decision whether or not to throw them out of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. If they've been convicted of Medicare fraud, their exclusion is mandatory. More likely than not, that would be a back-breaker for any company [because most of its profits come from sales to the federal government]. It's not going to voluntarily commit suicide by pleading to a criminal charge.

Lewis Morris, Chief Counsel, OIG, HHS

So they're likely to have brought their high-priced lawyers into the act and negotiated a settlement. What they then have to do is come to the office and convince us that it's better for the company to stay in business. We take a number of considerations into account, including whether the company is making critical or life-saving drugs, or if the company has a lot of innocent employees who knew nothing of the fraudulent conduct. Also, we consider whether or not the company has a good track record of treating the Medicare program fairly. If the answer to all those questions is yes, we'll generally negotiate a corporate integrity agreement [CIA].

Under the terms of the CIA, the company agrees to a wide range of measures including hiring a compliance officer, putting in compliance committees, and doing internal audits and training. The objective is to help the company rebuild its corporate culture. So instead of thinking it's okay to steal from Medicare, they focus on selling good products.

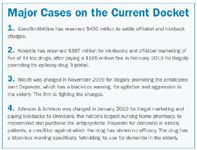

Major Cases on the Current Docket

When making the decision about whether to ban a company from Medicare and Medicaid, where do the interests of the patients fit in? If you exclude the company, don't you also exclude the drugs?

If the company is a maker of brand name drugs, they obviously have a stronger argument. If they're a generics manufacturer, they don't have that argument because someone else can step in tomorrow and fill that need. Interestingly, there is a more subtle response as well. We are considering a strategy that would say to a company, "All right, you have a particular life-saving drug and you're the only one that makes it. Sell it to somebody else. So you go out of business, but they'll pick up the cost and continue selling it."

What about the OIG's other options, such as relinquishing a drug's market exclusivity?

Well, if the reason a company illegally off-label-marketed its product was to gain a larger market share than appropriate prescribing would allow, they've basically cheated the marketplace. They've also put into circulation drugs not tested by the FDA. So we might say to the company, "You tried to cheat the market, so you have to agree to waive your exclusivity in return for not getting thrown out of our program."

There's also a third option. Let's say you're a big company and one of your subsidiaries is engaged in kickbacks to doctors or off-label marketing. We can tell the parent company, "You have to sell off that subsidiary, all of its trucks, loading docks, patents, microscopes, and everything else, because that part of your company was cheating our program and you don't get to continue to profit from that cheating." Those drugs that the subsidiary holds are valuable. Some other company will pick up the marketing rights. And if it takes six months to divest that subsidiary, we can give the parent company the six months. But at the end of six months, if you haven't divested, we're going to exclude.

We already do this to the large hospital chains like Tenet, which we believe has engaged in abusive behavior to patients, like invasive, medically unnecessary cardiovascular tests.

There's been talk that you're going to start going after individual executives at drug companies responsible for committing healthcare fraud. Is that true?

Yes. Part of our strategy is to say to companies, "It's not business as usual anymore." And the reason is that the first time around, we give everybody the benefit of the doubt. Everybody was entitled to make one mistake. And, particularly, in light of the importance of pharmaceuticals and the needs of our beneficiaries, that is a good policy.

However, when a company, for the second or third or fourth time, seems to have disregarded its commitment to integrity, we have to ask whether they're entitled to another bite of the apple.

We have been at this enforcement effort, this attempt to reform corporate cultures, for about a decade, and we can identify the recidivists. We've decided that we need to deal with them differently.

How do you determine that what has worked in the past is no longer working and other measures are needed?

Let me first say, emphatically, that we think that the majority of drug companies get it—they understand that the days of free dinner parties, all-expense-paid trips to play golf, and all that foolishness are over. And we applaud the drug industry for doing the right thing. But for that small group of companies—or executives—who think they know better, the measure of our success or failure is whether they show up at our door again with the same kind of problems that were before us previously.

Are the corporate integrity agreements having a beneficial effect?

I think they're having a great beneficial effect. And if you talked to any of the compliance officers at the companies that have been under CIAs, I think they would say the same thing. And if you had a side conversation with some of the sales people, I think they would tell you, "This really stinks." The good old days of being able to make your commission within two weeks at the expense of the Medicare program are largely gone.

So our strategy is working, all in all. But we have to always be asking whether we could do a better job. And when we are confronted with companies like Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Lilly, who have had previous problems and yet are back facing us again, we have to ask if we missed something.

Now, not every case where a company has come in for a second global settlement means that it has necessarily failed to embrace a better corporate culture. A lot of these problems are the result of corporate acquisitions where the parent company bought the proverbial "pig in a poke," and now they've got to pay the piper.

But there are other cases where the fraud is home grown, and where the company and its employees simply have not taken to heart the opportunity to reform their culture. So, what do we do about that group of companies? We talked about part of the remedy, which is to change the company's cost–benefit assessment. If they think there's profits to be made in off-label marketing of a drug, because they can increase their market share by 20 percent, even though the FDA told them not to—well, unless the settlement is going to cost you more than 20 percent of that product's sales, why would they stop doing it? So, to the credit of the Department of Justice, the cost of this illegal behavior is going up. Sound economic creatures—and everybody running corporate America is a sound economic creature—can do a new cost–benefit assessment and decide whether it's worth the risk.

Now what we've talked about so far is just the company's money. The other problem we have come to recognize is that as long as unscrupulous individual executives are getting their productivity bonus for getting that product over the top while the company is the one paying out the fine, the bad behavior is still being rewarded—and not a hell or a lot is going to change.

So, we've been thinking about ways to hold individuals accountable. Now, we aren't making up new law here. The concept of a corporate official being held personally responsible for the conduct of his or her company goes back to the 1940s. The Supreme Court has upheld this enforcement doctrine for the last 60 plus years. The principle is pretty commonsense. A corporation is just a piece of paper—it's people who make corporations run and who make decisions, good and bad. And we need to get individuals at the highest levels of these drug companies to understand that they are going to be held personally accountable if they were in a position to oversee conduct. If bad conduct occurred on their watch, they had the opportunity to do something about it, and they didn't.

Is the case of the three Purdue Pharma executives convicted of off-label marketing of OxyContin an example?

Yes. The three of them pled guilty to misdemeanor charges under the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act for introducing an altered substance into the market, the OxyContin. They maintained, and I believe the prosecutor agreed, that they did not personally engage in the off-label marketing. But as the chief medical officer, as the counsel, and as the COO, they had within their authority the ability to stop that misconduct and they didn't. So they pled guilty to misdemeanor charges under what would be called a "strict liability," and we subsequently excluded them from Medicare and Medicaid. So that's part of our new approach.

Does that mean these three executives are barred from working at other companies that do business with the government around Medicaid and Medicare?

The answer is a bit nuanced, but your core presumption is correct. The Medicare program will not pay for services that they deliver, provide, or otherwise cause to be delivered or provided for the period of exclusion. In the Purdue case, that was 12 years.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers are generally pretty removed from the direct provision of care, so the direct effect of an exclusion is less obvious. But the practical effect is that exclusion from our program sends a powerful message to executives that the federal government considers them untrustworthy. And what corporation would want to bring that sort of individual into a leadership position? Why would you hire a guy who's been convicted of cheating?

Now, there is a second theory. In addition to this legal theory of the "responsible corporate official," Congress has given us a specific authority to exclude someone who is an officer or a managing employee of a company that has been convicted of a healthcare-related offense. It doesn't mean that the company has to have been excluded, it just means convicted. So let's say you, as a company, enter into a misdemeanor plea for off-label marketing. We can exclude you, but we may choose to let you have a CIA instead. You've been convicted, but it's not a mandatory conviction.

I would say just about all the top 50 pharmas fall into that category.

Well, yes, they do. And this is where it's going to get interesting. Shouldn't there be a difference between a company that enters into a settlement under the civil False Claims Act and one that enters into a plea for criminal activities? Shouldn't we be treating the company that enters into a criminal plea more critically? But we now have a conundrum. This is a company that has pled guilty to criminal conduct. Yet if we exclude the company, we hurt patients, we hurt innocent employees, we limit access to life-saving drugs. So now the company is folding its arms and might smugly be thinking, "Ha, you can't get me, because I'm just too precious."

Our new response is going to say, "All right, you have pled guilty to a criminal charge. But we're no longer just going to let you write another check, and treat a criminal disposition the same as a civil resolution. The stakes have gone up. We are now going to take a look at your leadership, and ask who could have and should have stopped this criminal behavior?"

It is going to be a very fact-specific determination. We're going to do a lot of careful assessment of the merits, and apply justice. But in a case where a company has had the opportunity to do right and has taken a pass and pled guilty to a criminal charge, we're going to be asking why certain executives should be allowed to continue to run the company. And it's our expectation that other executives, both in that company and in other drug manufacturers, will say, "The cost of engaging in this criminal behavior has gone up because I could be out of a job." And that may be what changes the conversations in the corporate suites.

Do you prioritize your array of tools—selling meds, relinquishing exclusivity, holding individual executives accountable—in terms of severity. For example, if one doesn't work, then you go to the next? Or do you decide which to use based on the specific case?

We are going to look at the facts and the circumstances of a particular case, and decide which of our many tools will do the best job of protecting our beneficiaries and our program. But ultimately the Inspector General's Office is not here to mete out punishment. We are here to protect the integrity of the Medicare and Medicaid programs, to promote their efficiency and their effectiveness, and Congress has given us a mandate to remove from the program those who have abused our patients and demonstrated that they're not trustworthy.

How do you decide which cases to apply these responsible corporate official measures to? For example, what about the extensive off-label promotion of the atypical antipsychotics for the elderly in nursing homes, which may be responsible for a large number of deaths?

When we are trying to calculate an appropriate response to that sort of misconduct, one of the questions we ask is, "Did people get hurt?" In the Purdue executive case, one of the aggravating facts that we cited to justify the period of our exclusion was harm to patients. Now, I will tell you, just so the record's clear, that the Departmental Appeals Board concluded that we hadn't put forward sufficient direct evidence of patient harm—notwithstanding hundreds of newspaper articles about addiction and overdose.

These cases can present a real conundrum because physicians are free to prescribe a drug for any condition. So one of the causal connections that we have to establish is that but for the company's off-label marketing, the doctor would not have prescribed this drug. And it's often difficult to get a doctor to say, "I was duped. I just did what the drug company told me." More times than not, a doctor's going to say, "I knew exactly what I was doing. What, do you want me to get sued for malpractice? Are you nuts?"

The other causal connection we have to establish is between the bad act and the executives who are responsible, because in large corporations you've got lots of bureaucratic layers. So from a criminal standpoint, it can be extremely difficult to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that an executive broke the law unless you've got him on tape saying something. And most of them are too smart for that.

But in cases where we can show harm to a patient—such as ignoring black box warnings or marketing to a patient population that is specifically advised against—we can use the responsible corporate official statute.

How do you get information about potential cases of serious healthcare fraud, kickbacks, and the like?

Most notable is the whistleblower. The False Claims Act provides financial incentives for people to report fraud to the government. A significant part of our pharmaceutical fraud portfolio exists because people inside the company—salespeople, junior execs—have blown the whistle. The other way we build these cases is data mining. We're using highly sophisticated cutting-edge technology to identify aberrant practices and then start the process of investigating. If we see a substantial uptake in the prescription of a particular drug to a nursing home that wasn't present six weeks earlier, and we know that the drug is not approved for the main problems of the elderly, it doesn't mean it's illegal. Doctors could have decided they like it, but it might be worth dropping in on the nursing home. If the evidence shows that a salesman started coming in and handing out a brand of atypical antipsychotics like Chiclets, we might have ourselves a case.

It's been reported that the Purdue execs are appealing their exclusion. Do you think that once this new responsible corporate official initiative is set into motion, the courts will uphold the OIG judgments?

First, it's worth noting that while the Purdue executives are pursuing their appeal rights, which is absolutely appropriate, they are excluded right now.

Speaking more generally now rather than to the specifics of the Purdue case, the Supreme Court has a long history of ruling on administrative actions by federal agencies. There is very strong case law that lays out the criteria for evaluating whether an agency has acted arbitrarily and capriciously, whether it's provided adequate due process; and there is substantial deference to the agency's decision-making because the court recognizes that the agency is the expert.

The exclusion authority we've been talking about has been on the books for decades. We have a remarkably successful track record of pursuing these cases and being upheld, both at the Departmental Appeals Board and in District Court. I have a CrackerJack group of 75 lawyers who just love a challenge. So if a pharma exec wants to challenge his exclusion or in any way contest the merits of his criminal conviction, we welcome that.

Do you expect this new initiative to be at all controversial? How do you think the American people will look at top executives being given the boot because the corporations they run are engaged in fraudulent practices that harm patients?

Well, based on the reaction that we've gotten on the Hill, when people learned about the $2.3 billion Pfizer case, we weren't sent roses and congratulatory notes, we were asked, "Where were the executives?" And to take that a step further to your point about when you market a drug to a population which is highly vulnerable, and the FDA has told you not to, and it kills people, I'm guessing that the American population isn't going to have a lot of sympathy for a $500,000 exec who has now been told to get back to selling vinyl siding. That's my opinion, not necessarily the views of the Inspector General or the Department of Justice.

So the take-home message is that no one should be surprised if we begin to see executives having to take the rap. How soon? In the near future?

I would say in the middle future. And I want to stress that we're not just a bunch of cowboys here. Our job is to do justice—by assessing the facts and circumstances of each individual case. We need to be fully informed of the history of the case. A lot of the matters that come to us have been largely investigated as criminal frauds. Much of the information is grand jury testimony, and thus secret. So we start at somewhat of a disadvantage because we may not have the full story. And if we're going to do something as significant as potentially deprive an individual of his or her livelihood, we want to make sure we're doing the right thing.

So we will be approaching this with respect and caution to ensure that we do justice. But as we talked about at the beginning of this interview, we're coming to the conclusion that when a company has entered into a criminal disposition of its conduct and it's simply writing yet another check, we may not be getting the necessary message across to the company and its executives. I cannot tell you that we're going to do this in every case, because that would be foolhardy. But I hope that I have made it very clear that if what we're doing now isn't working, we're going to explore other options.

The Misinformation Maze: Navigating Public Health in the Digital Age

March 11th 2025Jennifer Butler, chief commercial officer of Pleio, discusses misinformation's threat to public health, where patients are turning for trustworthy health information, the industry's pivot to peer-to-patient strategies to educate patients, and more.

Navigating Distrust: Pharma in the Age of Social Media

February 18th 2025Ian Baer, Founder and CEO of Sooth, discusses how the growing distrust in social media will impact industry marketing strategies and the relationships between pharmaceutical companies and the patients they aim to serve. He also explains dark social, how to combat misinformation, closing the trust gap, and more.