- Pharmaceutical Executive-01-01-2008

- Volume 0

- Issue 0

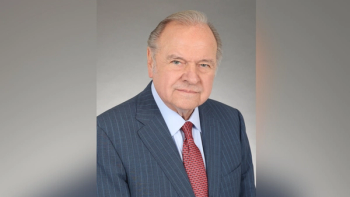

The Essential Essner

The departure of Wyeth's legendary CEO prompts a reflection on true leadership-and cooking

Wyeth's Bob Essner announced recently that he's relinquishing his long-held CEO spot to his longtime number two, Bernard Poussot. Now, Bob's not leaving pharma, or even Wyeth—where he'll serve as chairman. But what better time to acknowledge one of the industry's great leaders.

What a run! When Bob took the reins, Wyeth meant Premarin and Prempro and a stack of leftover Fen-Phen lawsuits. Under his guidance, it became a winner with solid franchises in CNS, respiratory, rheumatoid arthritis, and, increasingly, oncology.

Bob assembled and retained an exceptional commercial team: Joe Mahady, Geno Germano, Ulf Wiinberg, Jim Connolly, and Cavan Redmond. All highly recruitable for CEO or COO jobs elsewhere, yet all still with Wyeth. Show me another CEO with a comparable record! Together they launched significant drugs and pursued Essner's mission of developing and acquiring products that truly contribute to the betterment of health. No me-too's! No sir!

I've known Bob for 20 years. There's no flash to him. He looks like the history professor he always thought he would be, growing up back in Ohio. There's an intellectual weight to him, a mindfulness and clarity of thought. But he's no ivory-tower type, rather a brilliant marketer, a risk taker, and a hands-on manager who remembers that "executive" comes from the same root as "execute."

Sander Flaum

One of my most vivid memories of Bob Essner comes from my days at the Robert A. Becker agency. We had just won the Effexor business, after presenting a niche strategy for the drug. A few days later, I received a call from Bob. (I was in the Lincoln Tunnel, stuck behind a three-car pileup.) He thought I was looking too narrowly at the market.

The call (and the traffic jam) stretched to nearly an hour, with Bob taking me through the data and explaining his vision of the drug.

It was one of the most remarkable experiences I ever had in the ad business. Here was the COO of a major company, focusing his intellect and attention on me—not giving me orders, not critiquing my strategy, but trying to win me over, heart and mind, to his way of seeing things. It worked. He played the leader as I've seldom seen it played, and I was led. We changed the positioning, and guess what? Effexor was number one within two years.

Another memory: We had planned to have dinner in New York. A few days before our scheduled date, he called and said, "I have a better idea—let me cook dinner for you." And cook he did. As my wife and I sat there with Bob, his wife, and their three children, there was a real magic that had everything to do with the character and depth of the man, with his unfeigned interest in others, his effortless humility, and his obvious pleasure in working with his own two hands to honor and please his guests. Cooking may not be a core leadership skill, but the kind of heart and soul that went into the dinner we ate that night certainly are.

So, thanks for dinner, Bob. And for the work and the friendship. And for the example that so many of us try to live up to. Stay healthy and happy.

Articles in this issue

about 18 years ago

New Year, New Policy Challenges for Pharmaabout 18 years ago

Lincoln, Digger, and the Rest of the Gangabout 18 years ago

Oxfam Points Fingerabout 18 years ago

Pharma Forecast: Into the Woodsabout 18 years ago

Not Enough Scienceabout 18 years ago

Salesforce Survey 2008about 18 years ago

Outsource from the Insideabout 18 years ago

The Blogosphere: Too Hot for Pharma?about 18 years ago

R&D: Learning to ShareNewsletter

Lead with insight with the Pharmaceutical Executive newsletter, featuring strategic analysis, leadership trends, and market intelligence for biopharma decision-makers.