- Pharmaceutical Executive-01-01-2016

- Volume 36

- Issue 1

Ferring: The Quiet Company

Ferring Pharmaceuticals’ new manufacturing facility in Parsippany, NJ.

Is there virtue in obscurity? As media and investor coverage of biopharmaceuticals skirts closer to tabloid fodder, it’s a question worth asking. Over the years, Pharm Exec has chosen to focus on what we call the industry’s “stealth” players: mid-sized companies, often privately-held, with specialized expertise in areas like rare diseases. By aiming smaller, we have discovered some large truths about this industry, the most important of which is the sheer diversity of private-sector initiative in medicine. Such diversity extends beyond the science of drug development to the platforms and methods of drug delivery, itself a subtle but vital driver of innovation, and especially to organizational culture and management styles-a particularly rich vein of differentiation that we call “freedom to operate.”

Our latest incursion into the “stealth” space puts the spotlight on Swiss-based Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Two factors make its corporate brand stand out from big Pharma’s blurring shades of gray. The first is its scientific legacy as the first company to synthesize peptides-a natural hormone produced by the pituitary gland-into drugs that can treat a wide variety of endocrine-based disorders. The second is a tight, highly personalized ownership structure. Not only is Ferring privately held, 100% of its shares are owned by one individual, Frederik Paulsen, the son and namesake of a research physician from the North Sea Frisian islands whose “passion for peptides” led him to found the company in 1950. The Ferring name comes from the Frisian dialect pronunciation for the isolated, windswept island of Paulsen’s family home. In fact, company diaries handed out to Ferring’s 5,000 employees worldwide list days of the week in English, French, German and Frisian, the latter being a subtle but constant reminder of the company’s roots-an outpost of science in more ways than one.

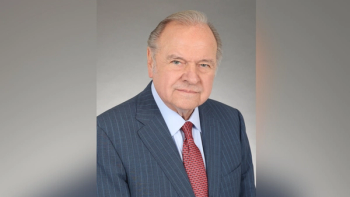

To explore what’s behind the Ferring mystique, Pharm Exec met recently with Michel Pettigrew, Chief Operating Officer (COO) and President of the company’s management Executive Board. Pettigrew, 62, is a native French Canadian and 30-year industry veteran whose credits include supervising the launch of Bristol-Myers Squibb’s iconic breast cancer drug Taxol.

In the following discussion, Pettigrew highlights the strategies that have doubled sales in the past six years, transforming a formerly Europe-centric business into a diversified global player with nearly €2 billion in revenues

spread among operations in 60 countries. This includes the US, which, on the merits of a strong reproductive health franchise, now accounts for nearly 30% of company sales. Through 2020, the plan is to invest heavily in R&D, at 16% of sales annually, and to grow sales at an average annual rate of 10%, to reach the €3 billion mark. On deck for success is a pipeline of 24 drugs in development and 14 major strategic collaborations, all centered on four therapeutic areas: reproductive health, where the goal is to become the No. 1 global player by sales; urology; gastroenterology; and endocrinology. Ferring is also investing heavily in manufacturing technology as well as related product sourcing work in APIs, peptides, and biologics; its expertise in producing more than 100 formulations, in different dosage forms, represents a delivery platform that is a competitive differentiator for a company of its size.

Finally, Pettigrew says he is spending more time on building in-house organizational capabilities, not just in attracting and maintaining talent but in creating a largely autonomous regional hub network centered on five priority markets: the US, China, Japan, Brazil, and India, in addition to the European home turf. Pettigrew relays that the tasks he has committed to are a bit easier-at least in terms of process -than those for his former counterparts at big Pharma. “The decision queue here begins-and ends-with one person, our chairman. And we are not for sale.”

PE: Ferring stands out as a curiosity in this industry for being a multi-billion dollar company owned by a single shareholder. How does this unique structure shape the company’s business model, culture, and decision-making process? Given your previous background in big Pharma, do you see any aspect of the Ferring operation worth emulating by other players in the industry?

Pettigrew: I joined Ferring 14 years ago. What struck me when I was approached to join the management team was the clarity of the company’s identity and mission. It was literally the expression of one man, Frederik Paulsen, our sole shareholder and owner. He inherited the position of Board Chairman from his father, Frederik Paulsen Sr., a physician who discovered the significant commercial potential of peptide hormones as an aid to healing and fighting many common infections and inflammatory conditions. Father and son share a fixation on leading the world with great science-I was told by Frederik within a minute of first meeting him that “for us, the science comes first. If the science behind the product is strong, a financial return will follow.”

This simple maxim is the reason why I joined the company. It remains true to our thinking to this day. Our business model is not driven by the need to demonstrate quarterly financial results. It means we are willing to take more time to make sure we are doing the right thing for patients and customers, which sometimes requires you subordinate the short-term for the long run.

Of course, you will find many other pharmaceutical companies touting the same commitments. What gives our position real heft is that we are free of the distractions and obligations that accompany status as a publicly-held enterprise. As 100% holder of the company’s shares, Frederik Paulsen has no rivals to deflect his thought process. And let’s be clear: Ferring is not a “family-owned” business. It is Frederik Paulsen’s business. In fact, Paulsen believes that family-owned firms are destined to fail in the long-run because successive generations carry different priorities; siblings grow apart. Eventually we expect that he will pass full ownership on to someone in the family, to continue the tradition of independence.

Ferring has never been for sale, it is not for sale currently, nor, barring a serious business reversal, will it likely be in the future. This fact has an enormous effect on how Ferring colleagues approach each work day. There is certainty built in to our work. The perspective is long term, so projects get completed. People feel less pressure to leave. When I consider all the disarray created by today’s surge in M&A activity, I see the ownership issue as a real driver of competitive differentiation for us. I have a finance background. It is my role to enforce discipline in how we manage our investments and direct resources. But I suspect this task is easier than my counterparts in other companies due to our Chairman’s singular insistence on following the science first.

PE: Can you document the impact this unique culture has had on financial results? How is it manifested in the type of people Ferring attracts to management-isn’t the absence of any ownership stake through the distribution of shares or options a disincentive to retaining top talent?

Pettigrew: When I started at Ferring in 2001, the company was posting annual revenues in the $400 million range. We are a long way from that today, as we expect sales of more than $2 billion for 2015. We remain private and our commitment to great science has

expanded into new therapeutic areas as well as building extra value for patients, right through the end of the product life cycle. And we are able to attract the most experienced, accomplished people to Ferring that we once thought were beyond our reach. Senior R&D and line managers from big Pharma want to review opportunities with us because they are frustrated by the way public companies must satisfy the short-term financial needs of institutional investors and shareholders.

PE: Can you describe your current role at Ferring? How is it different from your previous assignments in the industry as a line manager-does being a CEO require a different skill set?

Pettigrew: I must correct you-a distinctive feature of Ferring is we do not have a CEO. Instead, we opt for a more collegial approach to management, in which day-to-day activities are overseen by a five-member Executive Board consisting of myself, as Board President and COO, and four Executive Vice Presidents: our General Counsel, Chief Scientific Officer, Chief Medical Officer, and Chief Finance Officer.

We work mainly as a group. One of my responsibilities is to encourage each of us to contribute to decisions, even in areas outside our specific functional responsibilities. This is a bit of a test for me, as I am expected to convince the Board to follow my suggestions rather than deciding everything myself and expecting the functional leads to execute around it, which is the traditional notion of what a CEO does. In this way, we avoid the “standard practice” trap and allow fresh ideas to circulate.

I do everything to ensure this mindset is embraced further down in the management ranks. I’ve held a variety of positions in my 30 years in the industry, and the chief benefit of this exposure has been to make me culturally aware. I am tuned to appreciate the good things that people from diverse backgrounds are able to do, without necessarily telling them what to do. In other words, motivating people to succeed is the most important thing I do here.

Ferring’s operating structure puts a premium on this capability because we are so dispersed geographically. We operate in 56 countries. Each of our local businesses matter in terms of the ultimate bottom line. This contrasts to the big Pharma model, where you have a very large stake in the US along with five or six big markets in Europe and these together consume all the company’s energy and focus. Our approach puts much emphasis on allowing most decisions to be taken at the local level, closest to the customer. We encourage each country unit to act in an entrepreneurial manner, to set their own strategies and fix a budget on sales and profit contribution. The Executive Board approves the budget; what happens in between is up to the local team.

A practical manifestation of this is we have a highly decentralized approach to business development, including acquisitions, partnerships, and licensing. We give the countries a lot of flexibility in engaging around products and completing deals with other companies.

Of course, in our highly regulated industry, a balance must be struck to ensure that actions in the field don’t pose problems for the business overall. If just one affiliate has a compliance issue, it could rebound negatively and harm Ferring’s global reputation. The Board devotes a significant amount of time advising our local management teams on what we call a “culture of carefulness”-prudent risk-taking.

PE: Finding managers able to act independently within an entrepreneurial culture makes it very important that you choose right-the first time. By definition, there is little opportunity for micro-management. So how do you find the right people to head your country businesses?

Pettigrew: Handling “people” issues is the key component of my job. I think you will find CEOs at other companies saying the same thing. We devote much time here at HQ vetting every job candidate for a senior management job. They are seen by every member of the Executive Board, with the basic criteria being “will he or she make a good fit for the Ferring culture?” I personally interview two or three candidates a week, on average. My basic message to interviewees is that, while we have 48 nationalities and 30 languages represented here at Saint Prex HQ, we work extra hard to stay aligned. Ferring also has a bias toward starting people early in their careers. We have a special program where every year we recruit a select number of new graduates and put them on a two-year program that exposes them to different parts of the business, helping them figure where they want to apply their talents. I’d say most of my human capital activities are now devoted to the younger generation.

PE: Your experience gives you a certain perspective on the pace of change in the industry. What do you see as the most significant transitions taking place in the biopharma business model?

Pettigrew: We are on the cusp of some dramatic reversals in investor sentiment. The past five years has been all about companies like Valeant that rely on financial engineering as a growth strategy instead of the traditional reliance on big bets on science and R&D. It’s all about maximizing shareholder returns-end of story. I think the days are numbered for this model. The alternative is exemplified by my former employer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, which went through a fallow period where the pipeline was stressed and money was tight, but the commitment to science continued on track. BMS persevered and took big risks that are finally panning out. The company is destined to do very well for the next five to 10 years. Why? Because management focused on being strategic rather than opportunistic.

To me, this is the big differentiator. My philosophy is that being a good biopharma company means you have to be active in developing new drugs. You can’t borrow or acquire your way to long-term sustainability unless you are a generic house that has little choice but to consolidate. There are few other options to compensate for the dramatic drop in patented products ready to be genericized.

Even though I was trained in finance, I don’t believe that financial criteria necessarily determines what’s good for a company over time. I am also amazed at the steep acquisition prices being paid for assets today as well as the increasingly complex contract vehicles that introduce multi-billion dollar penalties in the event an M&A deal fails to close. In other words, actions supposedly taken on behalf of shareholders actually impose penalties on them. The break-up fee awarded to Shire when AbbVie’s management abandoned its takeover bid was so big that Shire used the proceeds to buy an entire pharma company, NPS. If I was on the Board of AbbVie, I’d feel compelled to ask its CEO, “how did you end up with that kind of deal?” It turned out to be a less than prudent use of shareholder money, I’d say.

PE: How does Ferring fit within this model favoring more patient-focused innovation? Are you big enough to fit comfortably in this new tent?

Pettigrew: There are many ways to be innovative today. One of Ferring’s strengths is its commitment to finding creative opportunities at every stage of the product life cycle. We have a stable of patent-protected medicines that represent an advance in the standard of care. Our mainstay is in branded generics, where we have established a global reputation for innovation in developing new forms of medicines that are better adapted to patient needs. A good example is Pentasa, for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Although it is off patent, we have, nevertheless, invested significant sums over the past 15 years to increase its efficacy for patients through better dosing. Today, Pentasa is the only treatment for these conditions that allows for maximum dosing strength on a convenient, one-a-day schedule. It basically sells itself because of the positive impact Pentasa has on patient compliance. Ferring believes there is a lot of growth left in this medicine. We continue to invest in clinical trial work to evidence its value.

The pricing pressure on branded generics, especially in Europe, demands that we strive for innovation in areas like manufacturing to keep our product costs down. Manufacturing efficiencies are part of our investment planning for Pentasa. Payers like what they see. The new dosing indications advance patient compliance, improving overall health outcomes, while we can price competitively due to the lower manufacturing costs we have achieved over the past few years. Frankly, the investments we have made make it too costly for the low-end commodity generics to vie for this space.

PE: Ferring revenues place it in the middle-rank of biopharma players in Europe. It shares a characteristic with this segment by being privately held. Is it your long-term goal to transition Ferring to big-time status, on a par with Novartis, Roche, and the other globally integrated giants?

Pettigrew: We are definitely committed to growing our business. The goal is to secure double-digit gains in revenues, of roughly 10 to 12%, consistently, year by year. Organic growth will continue to be the principal driver, from existing medicines and our R&D pipeline. The plan is on track: over the past two years, Ferring has launched three new products, including Cortiment for gastroenterology conditions and Cervidil for inducing labor in pregnancy. We are also excited about the Phase III trial results for our personalized fertility product, Rekovelle, which, based on the data, was accepted for a market licensing review by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on October 30. This puts us in a prospective position to launch Rekovelle later next year.

These products represent the specialty segment, serving a niche audience of patients with an unmet medical need. I think this is the right place to be. I would rather have a stable of 10 new products with revenues of $100 million each than one maturing blockbuster earning $1 billion that is in sight of losing its patent exclusivity. Actually, I like that Ferrings’ portfolio lacks a single “signature” drug, as it allows us to spread our risks across different product portfolios and therapy areas. Start small, launch, and improve-that’s our motto.

PE: Which therapeutic areas do you expect will drive this double-digit revenue growth?

Pettigrew: We intend to build on new first-in-class therapies like Rekovelle to become the world’s No. 1 company in infertility. We have three other areas of focus: urology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology. The commitment extends back to our founder Frederik Paulsen’s original vision of developing medicines based on synthesizing hypothalamus and pituitary-based peptide hormones. However, this does not imply we will never look at other areas. Ferring is an entrepreneurial enterprise, which by definition means we have to be opportunistic too.

PE: Isn’t reproductive health a hotly contested field where competition is a restraint on margin growth?

Pettigrew: In our view, it’s the opposite-two players have left the field recently. Our competition is now down to Merck & Co. and EMD Serono. Ferring is the only one of the three to market human-derived fertility medicines; the other two produce recombinant drugs based on molecular cloning. We also made a wise strategic bet about nine years ago to sponsor a major study comparing our approach to their artificial DNA model. The results showed very clearly that, if a woman wanted to get pregnant, her chances were best with our drug, Menopur.

PE: What role does business development activity-product licensing and external partnerships-play in Ferring’s growth strategy?

Pettigrew: Business development is definitely a part of our growth plan. We are always scouting for external assets that fit within our therapeutic profile. However, being privately held, I don’t have shares to exchange when we wish to make an acquisition. Our policy is to pay cash. That’s a big difference from the practice in publicly-held companies. If I make a $100 million mistake, I have just one shareholder -not 10,000-who is in a position to hold me accountable. So you can say our management is more exposed to risk.

PE: How does the US market figure in your plans?

Pettigrew: The US accounts for a third of our global business today. When I joined Ferring in 2000, it was just 6%. I am actively managing the US business, as I hold the title of CEO of Ferring USA. That came about in 2010, and since then we have grown sales from less than $200 million to $650 million this year-a threefold increase. Sometime in 2017, we anticipate the US will surpass Europe as our largest regional market.

I am bullish on the US. I have no doubt it is the one market where Ferring will grow fastest over the next 10 years. We started from a low base, which means that the faster our local business expands, the better off we will be in terms of margins, profits, and pricing. Simply put, if a company is not “all in” in the US, it is losing all out. Ferring is investing heavily there, including a new manufacturing facility in Parsippany, NJ, that complements our R&D campus in San Diego. We have created a strong market access capability -essential to doing well in the US -that has our pharmaceutical development, commercial, and manufacturing groups all operating under one roof. We don’t follow a matrix approach to management in the US-as CEO, I am responsible for everything.

PE: What about emerging country markets? Is Ferring sufficiently capitalized to ride the next wave of growth in these high potential geographies?

Pettigrew: We have identified four emerging countries where Ferring is looking for a bigger stake: China, for its sheer size and scope; India, as a source of new ideas, especially in manufacturing; Brazil, due to its bulging consumer demographic; and Russia, where the need for new medicines to repair declining life spans is particularly acute. I would be remiss without mentioning Japan as well, with its large, affluent and aging population.

All of these priority markets rely on Ferring’s distinct perspective on organizing for commercial success. There is a single leader for each country, with full responsibility for integrating the different functions. No silos here.

PE: Is there one particular aspect of your management style that has contributed the most to your success?

Pettigrew: I am not a micro-manager. My greatest satisfaction is to get something done without actually instructing people to do it-nor how to do it, or when. Influencing is what it is. When I see people I have managed out there leading on their own, I see it as a personal accomplishment of the highest order.

I am also a forward thinker, for which the best example is Ferring’s acquisition of Savient Pharmaceuticals’ Biotechnology General (BTG) manufacturing business back in 2005. The purchase, which few people thought we could pull off, allowed us to achieve three goals: (1) obtain full control over one of our licensed products, the growth hormone Zomacton, increasing our revenue base beyond the licensed geographies; (2) acquiring expertise in recombinant DNA and related manufacturing technologies, as a platform for future expansion into this important area for specialty biologic drugs, and accompanied by ownership of a state-of-the-art biologics facility in Israel; and (3) thus securing the high potential drug asset Euflexxa, a hyaluronic acid used to relieve pain in osteoarthritis of the knee, which we quickly launched in the US, where it helped diversify our product offerings beyond fertility. Today, Euflexxa accounts for a third of our US sales.

Most important, Ferring got a great deal on the price we paid for BTG. It stands as one of the best deals negotiated in the industry at the time, yet still today few people know about it.

PE: The biopharma sector is looking at an extended period of disruptive change. What are some key issues that industry has to keep its eye on to avoid being blindsided by trends that at the time seem insignificant?

Pettigrew: Getting a new product launch done right is the merit test for all companies today. The biggest bar to success is failing to anticipate actions by competitors. You would be surprised by the number of managers who assume that our therapeutic rivals will simply stand there and wait, doing nothing, until we act. Forget that. A competitor will always do something-today, many are willing to spend even more than the launch product to preempt any loss of market share.

Another concern I have is disruption from non-traditional players outside the industry. Our biggest long-term threat is not from fellow members of our own vertical but among companies that amass, interpret, and control information. It’s not the Mercks and Pfizers we must worry about, but Apple and Google. It’s probably true that today the two latter companies know more about US patients than any company involved in the business of healthcare. Their data allows them to analyze patient histories and to deduce patterns that will result in better targeting of a drug to the needs of an individual patient.

It’s important for drugmakers to get proactive in taking control of all this rich data, in the best interest of providers and patients, instead of seeing it as an enemy. Otherwise, Apple and Google, not the industry, will end up as the essential intermediary with the patient-the arbiters of innovation-while big Pharma finds itself confined to distribution and other low-end activities.

William Looney is Pharm Exec’s Editor-in-Chief. He can be reached at

Articles in this issue

about 10 years ago

Feeling the Heat: Pharm Exec's 2016 Industry Forecastabout 10 years ago

Feel the Earth Move Under Your Brand?about 10 years ago

Is the Hatch-Waxman System Broken?about 10 years ago

2015 FDA Drug Approvalsabout 10 years ago

Rough Road Ahead for Innovationabout 10 years ago

Country Report: Puerto Ricoabout 10 years ago

Pharmaceutical Executive, January 2016 Issue (PDF)Newsletter

Lead with insight with the Pharmaceutical Executive newsletter, featuring strategic analysis, leadership trends, and market intelligence for biopharma decision-makers.