8 Tipping Points: Pharm Exec’s 2019 Industry Forecast

Pharmaceutical Executive

Pharm Exec’s annual look at what lies ahead for the biopharma industry in the coming months examines eight key trends that are seemingly at tipping points in their evolution and poised to shape the life sciences landscape in 2019.

Welcome once again to Pharm Exec’s annual look at what’s ahead for the biopharma industry, where we hope the eight trends singled out for this year capture the pulse of change and opportunity impacting leaders and decision-makers in the life sciences the most. From technology and digital health (see accompanying guest column), to integration of healthcare delivery, to new-and big-competitors at the pharmacy level, to the tenuous countdown and aftermath of Brexit, these topics, profiled ahead and chosen with input from our Editorial Advisory Board, all represent key tipping points of sorts for the industry in the coming year. And with some, such as “emerging” biopharma, perhaps already tilted toward definitive change. Whatever the case may be, watching these areas unfold should be an interesting ride in 2019.

Vertical integration of payers, PBMs, and specialty pharma

Playing field for smaller biopharma has emerged

Gene therapies change pricing and payment model dynamics

Fight for Pharmacy: Amazon, Google’s immediate impact

Lifecycle management strategies evolve

Facing the realities of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit

Wading the digital therapeutic waters

More Coverage:

Finding the Right Digital Health Partner

A Deep Learning Curve

Keeping pace with data and AI

Broadly, industry’s uptake and optimization of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and data analytics has failed to match the hype that has surrounded the topic. While a September 2018 Frost & Sullivan report predicts that AI and cognitive computing will generate savings of over $150 billion for the healthcare industry by 2025, it also noted that uptake in healthcare IT has been slow due to strategic and technological challenges. So far, the report said, “only 15%–20% of end users have been actively using AI to drive real change in the way healthcare is delivered.”

With the industry moving tentatively into AI, Pharm Exec tapped into expert opinion that suggests company activities in this space over the next couple of years could be crucial in forging their path ahead. Those who are embracing and seeking to understand the true potential of AI and data may see their efforts begin to pay off. Others may find themselves facing that ominous decision: “Adapt or die.”

Making sense of data

Mark Lambrecht, director of the health and life sciences global practice at SAS, told Pharm Exec that he sees “a lot more realism coming along” from companies that began establishing in-house capabilities and data warehouses a couple of years ago, with company efforts now “maturing to the point where organizations understand what techniques they want to use,” with different architectures and technologies in place for different purposes. “They are following where the data is coming from and how it can help them move forward with clinical development or gain an understanding of what value their therapy brings to the market,” he adds.

Smaller biotech and pharma companies continue to be more innovative, however. For companies with smaller budgets, “automation is definitely a big driver in making the best use of the data and AI-whether that’s natural language processing or image analysis or newer techniques.” Small companies “don’t have armies of people to manually filter out the meaningful signals,” says Lambrecht, “so they want to deploy AI techniques on those big data sets. That leads to more efficient ways of looking at information and helps ensure that their scientists are looking at high-priority problems.”

While the absence of mature healthcare standards and the global variations in how data is structured and used remain “big problems” for pharma, there is positive news in that globalizing policies are driving harmonization, adds Lambrecht. “One example is the EU’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), which is having an effect globally in the way that the people are thinking about patient privacy. One of the downstream effects will be data harmonization and standardization. Another example is that the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) data principles, initiated in academia, are also becoming more important in the industry.”

AI in clinical development

Looking at the short-term future of clinical development, Lambrecht predicts that n-of-1 trials, or single-patient trials-randomized controlled crossover trials in a single patient-will come further to the fore from a data and AI perspective. N-of-1 trials investigate the efficacy or side-effect profiles of different interventions, with the goal of determining the optimal or best intervention for an individual patient using objective data-driven criteria. The hope is that every patient can have a specific therapy geared toward their genetic background and their disease, and patients can be matched with the right trial and the right therapies. “These n-of-1 trials offer the opportunity to gather a lot of data-genomics data, proteomics data-and do a lot of real-time analytics,” says Lambrecht.

Indeed, he adds, we are reaching a point when no clinical trial will be run without first consulting real-world data. “It will be part of the whole clinical development effort, from modeling and simulation and predicting where you need to go with your trial, in terms of geography and therapeutic area, to really understanding what the medicine under investigation does for patients.” Using real-world data generated from an abundance of sources-such as video data, demographic data, claims data, financial data-“will help companies understand more about the average patient and create therapies that improve patient outcomes and are impactful for society,” says Lambrecht.

Video data, particularly, will bring more analytics activity, with “streaming analytics becoming more pervasive.” Lambrecht explains: “Take a hospital that is using a robot for a surgical procedure; a lot of video data comes from that. Streaming analytics can be applied to that video data to help support the physician as he or she performs the surgery. In a similar manner, streaming analytics can be used for clinical development. It will help companies to trim down and keep just the data and information that is relevant.”

AI in drug discovery

Margaretta Colangelo, partner at Deep Knowledge Ventures, notes that biopharma companies were skeptical of the disruptive potential of AI in drug discovery (AI in DD), but by 2018 were showing “more interest in the sphere.” However, she says, companies are still moving very slowly in embedding advanced AI technologies into their internal R&D processes.

“The majority of biopharma professionals did not have AI or well-developed IT technologies integrated into their education,” says Colangelo. “Although biopharma companies have sufficient budgets to hire really strong AI specialists to start understanding this field, they are the most resistant to adopt new AI in DD technologies.”

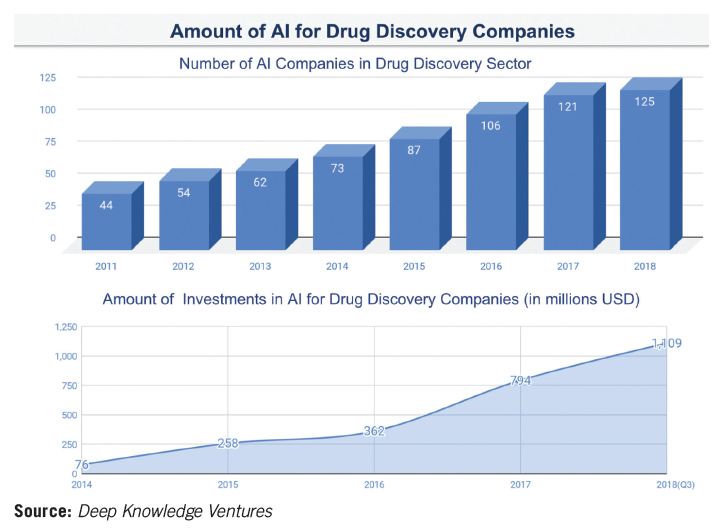

Noting that the industry famously takes a long time to make decisions, and even longer to transform its operating procedures in the face of new advancements and technologies, Colangelo adds, “Biopharma giants are just that-slow and lumbering entities, incapable of the kind of agility shown by the smaller and younger companies.” These smaller companies will continue to push advancements in AI in DD. Deep Knowledge Ventures expects, for example, to see 10–20 new AI in DD companies emerging in 2019, with the total number increasing from 125 in 2018 to around 140–150 by the end of 2019.

Colangelo points to generative adversarial networks (GANs) as the most significant AI technique to gain widespread traction in 2018. GANs pit a pair of neural networks with machine intelligence-one generative, the other discriminative-against each other in a “competition,” potentially producing outputs over time that are beyond human capability. While GANs have been used in the generation of images and music, in 2017, scientists from Mail.Ru Group, Insilico Medicine, and MIPT applied a neural network to create new pharmaceutical medicines with the desired characteristics.

GANs, Colangelo explains, “grew from an extremely new, next-generation technology at the beginning of 2018 to being embraced as the leading frontier of AI and deep learning-and the de-facto standard for modern, advanced AI-by the end of the year.” She predicts that in 2019–2020, GANs will be surpassed by the next generation of novel AI technologies, “resulting in new techniques that are as far advanced in relation to GANs as GANs are currently to normal recombinant neural networks.”

So far, only a “select few” AI in DD companies are applying GANs as a core part of their R&D processes, because the high level of expertise required means hiring very strong AI specialists-“a scarce resource in the industry right now,” says Colangelo. In order to survive in the coming years, the major biopharma companies will need to “reinvent themselves completely,” adopting AI as the core component of their R&D, allocating substantial budgets to hire the best AI specialists and proactively keeping pace with new AI advancements.

While a few existing biopharma corporations will prove capable of surmounting this challenge, “the rest will prove incapable and will be fated to die out as a result,” warns Colangelo. She adds, portentously, “No area of biotech and healthcare will be untouched by AI techniques. They will disrupt all niches entirely.”

- Julian Upton

New Era in Drug Management

Vertical integration of payers, PBMs, and specialty pharma

In early December 2017, CVS Health and Aetna announced their intent to merge in a $69 billion deal. Soon after, in March 2018, Cigna and Express Scripts announced their vertical integration at a $52 billion price tag. As of this writing, both mergers have yet to close. CVS Health/Aetna is much closer, having been approved by a number of state regulators and a divesture of Medicare Part D prescription drug plan business for individuals required by the US Department of Justice. Cigna/Express Scripts extended its merger deadline from December 9, 2018, to June 8, 2019, but has also gained some state approvals. While the extension now makes the vertical integration of payers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and specialty pharma too early to call a homerun 2019 trend, with the forward motion of the merger approvals and already set-in-motion programs by each of these PBMs, the impact of the vertical integrations on pharmaceutical manufacturers is well in sight. Outside of the big two, other integrations include UnitedHealthcare/OptumRx and Blue Cross Blue Shield with Prime Therapeutics. However, because Prime is owned by a number of BCBS plans but not all of them, it is slightly different.

According to Cathy Kelly, who regularly reports on PBMs in her role as senior editor for The Pink Sheet, the newest mergers are not likely to result in significantly more members or covered “lives” for any of the players. CVS had already been managing some duties for Aetna’s pharmacy benefit along with its own internal PBM, and Express Scripts had recently lost Anthem as its largest client, so the addition of Cigna members more or

Cathy Kelly

less brought them back to equal.

But what the combinations could lead to is a greater allocation of PBMs managing medical benefit drugs, rather than just drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit. Kelly suggests that with their ability to see the claims coming across the insurers database, the PBM insight into how to better manage or control the costs of the more complicated physician-delivered drug landscape, which is usually in the scope of the specialty drugs, is a potential.

On the other hand, one challenge for the PBMs involved in the pending mergers is that the combinations lose clients because of the actual or perceived competition. For example, insurers that don’t want to use Express Scripts as their PBM because of the Cigna relationship.

PBMs and manufacturers are bracing for a major disruption in the current system of drug contracting, with possible regulatory action coming from the Trump administration to restrict the use of rebates. In the meantime, the major PBMs are introducing programs that aim to reduce the reliance on rebates. The most apparent trend emerging that warrants pharmaceutical executive attention are those programs.

As Kelly told Pharm Exec, “PBMs have been taking a lot of heat the past couple of years over rebates.” And our own Editorial Advisory Board (EAB) suggested that the increased pressure on the PBM is leading many to challenge or question PBMs’ power in the supply chain. Kelly acknowledged that pressure is due, in large part, to manufacturers’ efforts. “The manufacturers have worked very hard on educating the public on how the supply chain works, how they have to build money back into their list prices to account for the rebates. They have done a very effective job.”

But PBMs came back swinging at the end of 2018, and seem to be swaying government opinion, if not public opinion. Express Scripts announced that as of Jan. 1, it will offer employers the option of using a formulary that would prefer lower-cost alternatives to expensive brands and would exclude the brands from coverage as a way to effectively lower prices without violating the terms of rebate agreements already in place. A press release stated, “The Express Scripts’ National Preferred Flex Formulary provides a way for plans to cover lower list price products, such as new authorized alternatives that drugmakers are bringing to the market and reduce reliance on rebated brand products.”

The CVS response, announced in early December, is its new approach to pricing, called guaranteed net cost pricing, described in a press release as guaranteeing “the client’s average spend per prescription, after rebates and discounts, across each distribution channel-retail, mail order, and specialty pharmacy…with the guaranteed net cost model, clients continue to have the option to implement point-of-sale rebates to provide plan members visibility into the net costs of their medication.”

As Kelly explains, both the Flex Formulary and the guaranteed net cost pricing are options for employers, so the uptake of the programs may not be known for some time. “PBMs are usually not forthcoming about clients, but these are high-profile programs, so they may want to put that information out there.” However, the net overall effect of the PBM programs, as well as their mega-mergers, will only start to be realized this year.

Will PBMs be able to improve their overall public perception in 2019? Again, time will tell. As Merck & Co. CEO Kenneth Frazier was quoted in this article, “I mean no disrespect to anyone else in the supply chain, but I know how hard it is to make my 50 cents on the dollar. I have to invent something that’s never existed in the history of the world. And I have to ask my shareholders to be patient with their capital. I think that the system has got to change.”

- Lisa Henderson

Past the Tipping Point

Playing field for smaller biopharma has emerged

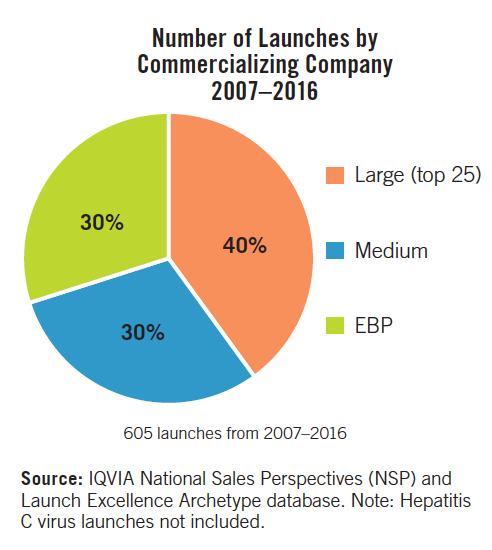

The FDA is now approving more drugs and biologics coming from companies that have never had an FDA approval before. Pharm Exec Editorial Advisory Board (EAB) member Kenneth Kaitin, director and professor, Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) at Tufts University, says, “The landscape is shifting now beyond the tipping point and what that means to the traditional drug development ecosystem. How do these smaller companies get feedback on development and on launch?”

As has been widely noted in Pharm Exec, the FDA is also approving more new molecular entities (NMEs) that serve the orphan or unmet disease space, much of which is dominated by the biotech and smaller or emerging biopharma (EBP) market.

Tufts’ November/December 2018 CSDD Impact Report tackled this topic, outlining the following facts:

- Since 2002, pharma partnerships have been the largest funding source for biotech development, providing 44% of all biotech financing last year.

- Biotech products most recently accounted for 41% of annual revenue for the top 20 pharma companies. Author of the report, Ronald Evens, PharmD, adjunct research professor at Tufts CSDD, noted: “The biotech-pharma relationship is likely to grow, as the demand for innovative treatments to address a host of unmet medical needs expands.”

- Biotech products now account for more than 30% of all new US drug and biologic approvals.

- From 2007 through 2017, biotech sales as a share of all company sales have almost doubled, from 23% to 41% among the top 20 pharma.

- As of August, Phase III clinical trials were underway on 532 biotech products spanning 264 indications.

- Biotech products accounted for 31% of the 457 drugs with orphan designations that have won US marketing approval since 1983, a share that is expected to grow in the medium to long term.

With the increase in smaller biopharma launches and targeted therapies, the logical progression would be a lessened need for big pharma’s salesforce. However, the Tufts numbers don’t back that up. Sanjiv Sharma, vice president, North America Commercial Operations for HLS Therapeutics, and also an EAB member, says that big pharma will not lose its role, in that “they have the ability to break through the noise and if they need a Phase IV, where large pharma dominates in the KOLs (key opinion leaders), then that will still work. As a buyer or partner, large pharma still has the upper hand.”

While the traditional pharma market has covered its own bases with licensing, sales, partnerships, and the like

with biotech and EBPs, where do the third-party providers meet the needs of the small achievers? Some speculate that because of smaller patient pools and more complex drug delivery requirements, these EBPs don’t require the level of scale that traditional contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs), contract research organizations (CROs), or market access offer.

CROs are facing a similar criticism that they have faced all along when contracting with smaller pharma, and that is the lack of attention if the company’s product portfolio is not large. Big pharma equals big CRO is the mantra, and the outcome of the preferred provider contracting relationships. This whole new world of biotech and EBPs that need CROs’ help for drug development is causing some concerns among their C-suites. As noted in this article, based on a roundtable from CBI’s Finance and Accounting for Bioscience Companies conference held in Boston in late September, CFOs have common concerns of being billed for patient tests not even within their protocol or compounds relevance; not delivering on time or on budget; and requiring a lot more oversight than originally thought or planned for. CBI is hosting a conference specific to EBPs and CROs oversight in Boston in early March.

With all the forward motion with biotechs and EBPs and the clear positive performance with FDA approvals, the only challenge is in the markets. Les Funtleyder, portfolio manager for Esquared Asset Management, and EAB member, says, “The last two years have had record capital-raising for the biotech/emerging biopharma. If there is any volatility, or capital sources dry up, the ultimate downstream effect on large pharma would change.”

- Lisa Henderson

Curative Care Upending System

Gene therapies change pricing and payment model dynamics

The continued advancement of curative cell and gene therapies onto the market stage is clearly challenging traditional pharmaceutical payment and reimbursement structures, driving new strategies, and ultimately moving this topic well beyond simply the initial price-or wholesale acquisition cost (WAC)-of a treatment.

While there remains many publicized developments focused purely on pricing, including the return this month of price hikes by several big pharma companies after holding the line on increases for a period last year amid pressure from the Trump administration; Medicare Part B drug reform, where the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is considering a new reference/“International Pricing Index” (IPI) payment model that would link reimbursement to the average price paid in foreign industrial nations; and more state laws passed seeking greater pricing transparency, at the heart of this issue, experts say, is the emergence in recent years of novel and expensive treatments with potential one-time administration and lifelong benefits. CAR-T drugs for cancer, other immuno-oncology and immunotherapy agents, gene therapy, and vaccines-many addressing orphan and ultra-rare diseases-have changed the paradigm of how the current healthcare payment/reimbursement system operates, one built on high-volume transactions. Curative-type products approved so far typically have front-loaded or high upfront pricing.

“[These drugs] are pushing the issue to, ‘how do I, as a payer, know that I’m actually going to get the value that you’re asking me to pay for this?” Debbie Warner, vice president, commercial consulting, Kantar Health, told Pharm Exec.

In 2019, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), which provides clinical and cost-effectiveness analyses of treatments and other medical services, will be examining that same question more closely as it applies to curative-intended therapies and whether it needs to adjust its value assessment framework accordingly. For example, should more latitude be allowed for the cost per quality-adjusted life year in certain cases? After mixed cost-value evaluations of gene therapies last year, ICER has taken some criticism for needing to update its framework to better gauge these kinds of therapies.

Ron Philip, chief commercial officer for Spark Therapeutics, which, in late 2017, won approval for Luxturna, the first-ever targeted gene therapy approved in the US, says new modalities such as gene therapy-in Luxturna’s case, a one-time treatment for inherited retinal blindness for patients with the rare RPE65 gene mutation-are disrupting the current healthcare ecosystem, where the tendency for most stakeholders is to get stuck on the upfront pricing element.

“When you think about the lifetime costs of that patient on therapy and compare it to a one-time treatment that [a company] gets a certain amount of money for upfront, the savings to the healthcare system could be tremendous,” Philip told Pharm Exec. “We’re advocating for the changes that we think are needed in order to make these one-time therapies progress in a more viable healthcare system. …Our intention is to get coverage for the patient. Every day that goes by is one more day with the retinal cell that could be degenerating. Speed is of the essence for us.”

Philip, a former Pfizer executive, who joined Spark in 2017, says the biotech is championing for changes in Medicaid best price and US price-reporting regulations, addressing aspects such as portability, which is when patients move from one health plan to another. Treatment durability-and restrictions on how many years out companies will want to structure durability reads-is also a concern when assessing one-time therapies.

Last January, Spark announced a list price for Luxturna of $850,000 per one-off treatment, or $425,000 per eye. To ease costs for patients and payers, Spark has a rebate deal in place with Harvard Pilgrim, which ties Luxturna’s cost to clinical outcome. Specifically, it will pay back 20% of the price in the form of a rebate if visual improvement objectives are not reached within two and a half years. Spark has also created what it calls Path, a flexible contracting arrangement between payers and treatment centers, where they can bypass the traditional buy-and-bill process, which can sometimes be taken advantage of in the form of price markups. In addition, Spark has submitted a proposal to CMS to allow Luxturna payments to be spread out over time. With commercial payers, Luxturna has 85% percent coverage, according to Philip, achieving that over a nine-month period. The last public update by Spark cited 50% coverage for Luxturna on the government side and the company plans to add more coverage in the coming months.

Some believe Spark’s value framework for Luxturna, which was approved in November in Europe (Novartis will commercialize the product in that region), can serve as a model or blueprint for innovative pricing plans for curative-intended therapies. “It’s a model based on the current system. We, as well as other manufacturers, I think it’s safe to say, would like there to be a new model that would allow us to provide more flexibility to help address some of the needs within the healthcare system,” says Philip, noting, in terms of rebates, that Spark would like its one for Luxturna to be higher to “show to the insurers that we have good faith in this product,” but are constricted by best-price and average manufacturer price-reporting restrictions. “With anything else, when you’re bringing in a new innovation, the world takes a little while to catch up. We need it to catch up to fully value what these treatments are bringing to the landscape.”

Though not a one-time therapy, the accelerated approval granted by FDA in November of Bayer and Loxo Oncology’s targeted cancer drug, Vitrakvi, is another example of the sticker shock related to the costs of orphan treatments. Vitrakvi, the first-ever agent to receive a “tumor-agnostic” indication at the time of approval, treats patients with solid tumors that have neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene fusion without a known acquired resistance mutation. The oral version, according to published reports, is priced at $32,800 per month before discounts. Like Spark, Bayer provides access programs-one which refunds payment when patients don’t respond to Vitrakvi within 90 days, and another that provides reimbursement support and patient assistance services.

Payers have also put new strategies in place to respond to growing orphan-drug expenditures. For example, a report in Managed Healthcare Executive notes that insurers have employed benefit design changes to manage utilization and the cost associated with these products. Changes include formulary restriction and specialty tiers, shifting from copayments to coinsurance, and prior authorization.

Warner says an approach used by developers of anticipated late-stage therapies may be testing the pricing waters, in essence trial-ballooning a prospective price tag for the product before it’s potential regulatory approval. For example, Novartis’s investigational gene therapy, Zolgensma, for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which could be greenlighted by FDA as early as May, is reportedly set to be one of the most expensive medicines on the market. Novartis may put a one-time cost of $4 million to $5 million on Zolgensma, designated a breakthrough therapy by FDA. The company says that price, based on its cost-effectiveness model weighing a 10-year cost of treatment against quality-adjusted life years, outweighs the long-term costs of caring for SMA patients over a decade period with the current standard of care, Biogen’s Spinraza, the first gene therapy approved for SMA; Spinraza consists of quarterly intrathecal injections and holds a list price of $750,000 for the first year and roughly $375,000 for subsequent years. SMA, an inherited disease that can be fatal, is triggered by a defective or missing gene known as SMN1.

“I think that they’re putting the price out there to get a lot of input in terms of how will it play in the court of public opinion, what are the reactions-to spark some discussion and negotiation and perhaps desensitizing the payers and the public a bit so that they’re not announcing this on the heels of a launch,” says Warner, who before joining Kantar Health, spent more than 13 years at AstraZeneca.

Should it win approval, Novartis could end up implementing some form of an outcomes- or value-based contracting arrangement for Zolgensma. In general, these agreements between payers and drug manufacturers, an area we’ve covered extensively in Pharm Exec (see here), continue to build steam with various pilot programs initiated, particularly in the diabetes and cardiovascular disease space. Overall, however, these deals remain relatively in the infancy stages, experts say. Depending on the disease targeted, a wide range of variables are still at play, such as access to patient records in some cases, as well as practical questions around how both sides can agree on what kinds of outcomes to measure. Though many drugmakers have dedicated teams with capabilities and resources in health economics and outcomes research and real-world evidence-and payers also have extensive experience in mining their data-the job of accessing, collecting, and interpreting data, making correlations to existing technology to help treatment centers measure certain outcomes, and monitoring patient data over time presents significant challenges.

“The devil is in the details with regard to getting the data and being able to tease apart whether there are confounding factors,” Warner told Pharm Exec. “The more subjective the evaluation is or the more patient variability there is, the more difficult it’s going to be to do anything at a standard level in terms of an outcomes-based contract.”

Philip believes it’s critical for companies to begin mapping out their health outcomes strategies for a product in the early phases of clinical development. “I’ve always thought that you’re selling on data and you’re giving the product away for free,” he says. “Data is what sells. You have different consumers of that data. HCPs want a certain set of data, patients want a certain set of data, and payers also want a certain set of data. That data needs to be encapsulated into your clinical trial program so that when you come to launch, you’re moving forward with things that the payer actually cares about. The flexibility on some of the different solutions will allow you to use that data to address their needs.”

And, in turn, strengthen manufacturer-payer alignment around the importance, in today’s “patient-centric” climate, of continuous monitoring and measurement of outcomes over time. “We’re going toward that model,” Philip told Pharm Exec. “I don’t think we’re going back to where we were in the ’80s, where people just took a pill and hoped that it worked, and you just paid the price. For gene therapies, I don’t think this new model is ever going to go away.”

- Michael Christel

Fight for the Pharmacy

Gauging Amazon and Google’s immediate impact

It seems like almost every day, there is a strongly-worded headline declaring an Amazon or Google-type company’s foray into the healthcare industry. Or an article that touts a new partnership geared toward competing with these organizations for a share of the consumer marketplace.

Examples include Amazon’s acquisition of PillPack, a full-service pharmacy that sorts and delivers medication right to a person’s door, and CVS’s late 2018 announcement that it was testing CarePass-a membership in the Boston area that costs $5-a-month, or $48 annually, and includes free delivery on most online purchases and prescriptions, access to a pharmacist helpline, a 20% discount on all CVS-branded products, and a monthly $10 coupon.

Another example is grocery store chain Kroger’s exploratory pilot partnership with Walgreens, in which they plan to collaborate “on a new format and concept that combines Kroger’s role as America’s grocer and food authority with Walgreens global expertise in pharmacy, health, and beauty,” according to a press release last fall.

All these cases seem to mention the pharmaceutical industry in some way, but the partnerships don’t go as far as creating a major distribution or therapeutic disruption. So, should pharma C-suite executives be concerned about these moves, because they are impacting the ultimate product end user-the patient? The answer is: yes, and no.

Experts who spoke with Pharm Exec suggest that drug manufacturers need to keep a close eye on what is happening, but should not immediately feel threatened by the presence of Amazon, Google, or the like compared to other players in the healthcare space-despite the likelihood that the fight for the patient from a supply chain perspective will continue to garner attention throughout 2019.

While none of these high-tech giants are creating a commercial therapeutic, there could be an impact down the road for life sciences companies when it comes to pricing, as well as how their product gets to the patient.

“It’s very important to recognize that Amazon, etc. are going first for the pharmacy, not the pharmaceutical companies,” says Pratap Khedkar, managing principal at ZS Associates. “That’s distribution vs. manufacturing-a huge difference in investment/risk/margins/ROE/business models. Just because Walmart decided to sell light bulbs, it did not nullify GE’s ability to invent and make them. There will, of course, be a strong price pressure from this, but it will be felt mostly by the generics now, not the brands-unless Amazon enters payer-style rebate negotiation, which has not happened yet.”

However, that doesn’t mean pharma manufacturers should be complacent. “They now have to recognize the potential power of these players when it comes to pharmacy,” says Ashraf Shehata, advisory principal at KPMG. “Some of these tech players may have assets that can be deployed when it comes to patient education, medication adherence, or improving patient engagement.”

Shehata, who works with healthcare and payer organizations, explained that Amazon and Google are both well capitalized, don’t have the legacy assets that retail chains have, and understand customers very well. They also have the means to invest in technology and people to create opportunities to reach patients. Amazon also has leading-edge technology to manage a supply chain.

“This can be very disruptive to retail pharmacies and we’ve seen a great deal of merger activity in the healthcare sector to better position themselves to counter new entrants into healthcare,” says Sheheta.

What drugmakers do need to pay close attention to is the influence Amazon and Google and these non-traditional partnerships will have on the industry as a whole-the shift to understanding the patient from a consumer perspective.

“Consumers of pharmacy benefits are facing a rapid evolution of the supply chain,” says Albert Thigpen, vice president, president and chief operating officer of the pharmacy benefit management (PBM) division of Diplomat Pharmacy. “Potential pharmacy alternatives like Amazon, vertically integrated health plan models (UnitedHealthcare, CVS/Aetna, ESI/Cigna), and an ever-increasing use of high deductible health plans where consumers pay the majority of the cost are making the choice of pharmacy more of a consumer-based model. Key stakeholders such as pharma should pay close attention to these changes. The business model that provides actionable information and empowers the consumer to make those changes will be the most sustainable model. Amazon has proven this in the retail segment already.”

- Michelle Maskaly

From Zero to Life

Lifecycle management strategies evolve

Calculated attempts to extend a drug’s lifecycle, and defend its patent is nothing new to the pharmaceutical industry. It has been practiced for years through the legal system, Phase IV clinical trials, and generating evidence for new indications, among other avenues.

But experts say the number of companies taking advantage of this has increased significantly, which has more people talking about it publicly, and looking for new strategies in lifecycle management.

“The rationale is the relative cost of spending $2.6 billion to create a new drug with all the uncertainty of approval vs. the few tens of millions to extend life by a few years or even months without approval uncertainty; plus it is a way to help short-term revenues,” says Pratap Khedkar, managing principal at ZS Associates. “It takes 8.5 years to get a new drug to market on average from the NCE (new chemical entity) stage and even in oncology, the odds of approval from Phase II/III is only 8%-10%.”

The tools available to help facilitate product lifecycle have also expanded. Most notable, and what makes it something to watch evolve in 2019, is that as the lines blur between technology and pharma, new ways of delivering a therapy are being developed to extend the lifecycle.

“We’re seeing effective strategies that focus on patient engagement and creating more value for consumers,” says Jodi Reynolds, principal, life sciences and healthcare, Deloitte Consulting. “For example, companies that have drugs that have a device element, like an inhaler or an injectable, are advancing those devices to make them smart and linked to an app. That creates an ecosystem that provides further value to the consumer just by taking the drug. It also protects the brand-brand affinity is key to extending the life of a patented drug and things that add value for consumers provide a level of comfort.”

One example of how technology has extended the lifecycle of a therapy is Bayer’s autoinjector for its multiple sclerosis (MS) drug, Betaseron, which was approved by FDA in 1993, and went off patent in 2016. A year earlier, Bayer announced that it won FDA premarket approval for its Betaconnect electronic autoinjector. At the time, the company was also facing competition from new oral treatments such as Biogen’s Tecfidera.

In May 2017, FDA approved a supplemental biologics license application for Bayer’s myBETAapp and the BETACONNECT Navigator. According to a company press release, with this software in relapsing-remitting MS, people using the electronic Betaconnect autoinjector to administer Betaseron can use Bluetooth technology to connect their current autoinjector to the myBETAapp on their mobile device or computer.

Last April, Bayer executives were featured speakers at the Asembia Specialty Pharmacy Summit, where they spoke about the technology and how it added a new lifecycle to a 20-something-year-old drug.

Generic competition

To protect their patents, some companies are also creating branded generics, which, experts say, can be a double-edged sword.

“One of the biggest positives is leveraging the consumer’s comfort and familiarity with the brand, so when there’s competition, it still stands out,” says Faith Glazier, principal, generics segment leader, Deloitte Consulting. “Consumer perception adds a level of trust and familiarity.”

But the down side is that it will cannibalize the brand itself.

“Any thought of maintaining the uniqueness of the brand is sacrificed,” says Glazier. “It could be a useful strategy at times, however. When companies want to be able to lower a price point without showing dramatic price drop on the branded product, for example, they can do it for one dose or dose size of the generic and leave the branded product alone.”

Speaking of generics, manufacturers of these drugs are also looking for ways to extend the lifecycle of their products.

“The generic market is deflationary,” says Edward Allera, co-chair of Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney PC’s FDA practice group and a former associate chief counsel at FDA. “Companies in that space are looking for new opportunities. The logical step is to move into the 505(b)(2) space, which is analogous to the product lifecycle extension space.”

Allera explained that the normal first step is extended-release versions of oral tablets. Then companies look for other new dosage forms that make the active ingredient safer, such as improving the bioavailability or the solubility.

“Then they look for new indications that require clinical trials and can use different salts or esters, so that they can get additional market exclusivity and perhaps pediatric exclusivity,” says Allera. “Also, they may seek a new indication for an old product that can be genetically modified to produce an orphan-drug approval. Numerous combinations and permutations of technology and drugs are available. The space is wide open.”

Interesting approaches

There have been some untraditional approaches that innovator companies have taken to protect themselves against generic competition. Chip Davis, CEO of the Association for Accessible Medicines, which represents generic drug manufacturers across the globe, says the most egregious example of anti-competitive behavior may be Allergan’s recent ploy to thwart a challenge to a patent for its blockbuster drug, Restasis, by transferring the product’s intellectual property to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe in order to “rent” the tribe’s sovereign immunity from legal proceedings.

Davis wasn’t the only harsh critic of the move. Allergan received backlash from not only government leaders, but also US agencies and court systems that oversee these matters. In May of 2018, retail pharmacies legally challenged the company, alleging anti-trust violations.

While the decision to do this caused great controversy, experts say the industry should expect to see more out-of-the-box moves in this space.

- Michelle Maskaly

Withdrawal Symptoms

Facing the realities of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit

Given the Brexit turmoil that has consumed the UK for the last two-and-a-half years, it seemed optimistic, ambitious even, to predict in Pharm Exec’s last Industry Outlook that the country would be much closer to agreeing on a withdrawal strategy by the end of 2018. But as that date passed, and with just three months to go before the UK leaves the European Union (at 11 p.m. GMT, March 29, 2019), one might have expected at least some further clarity around the withdrawal deal.

That faint hope, however, seemed to evaporate when Prime Minister Theresa May postponed a Dec. 11 crunch vote to get her controversially compromised version of the deal through the House of Commons. May was not expected to get the backing the government needed-hence her decision to buy more time-but the postponement created further chaos, with the PM forced to delay her plea-bargaining tour of Europe while she fought to retain the leadership of her party in a confidence vote. May went on to win the backing of most of her MPs, but this did little to quell the sense of disorder. While she gave an assurance that the Commons vote would take place no later than Jan. 21, she was accused of “running down the clock,” and, in the words of one of her government’s rebels, effectively “giving the country [and] Parliament no choice at all-except between her deal and no deal at all.”

At the time of going to press, the prospect of a “no deal” between the UK and the EU looks like a real possibility. As such, pharma, like other industries with “skin in the game,” is “upping its contingency planning-and hoping,” says Pharm Exec’s Brussels correspondent, Reflector. “Every month, around 45 million packs of medicines leave the UK destined for patients in Europe, with 37 million packs heading the opposite way. In total, that is around 1 billion packs of medicine crossing the border between the UK and the EU each year,” he explains.

That sort of traffic will be desperately vulnerable to the new border checks that a no-deal scenario would impose. This is not just an economic issue for manufacturers and customers; for the healthcare sector, the primary concerns are patient safety and public health, he adds. “The industry has invested in fall-back positions-but this is not enough. The authorities have to act, too,” says Reflector.

To counter the risk of customs and other checks at ports and borders causing delays-together with the possible suspension of air flights and, thus, the delivery of medicines and time-critical clinical trial materials to patients-Reflector points to a series of industry demands to “mitigate the damage that will arise from a disorderly UK disengagement from Europe.” Among them is the call for ports to provide fast-track lanes or priority routes for medicines; the temporary exemption of medicines and clinical trial materials from any new customs and borders

checks; the need for the European Air Safety Authority to recognize certificates issued in the UK to ensure that planes can continue to fly; and for the EU to continue to recognize UK-based testing-at least for the time being-as not all companies will manage to relocate batch-release testing to the EU by March 30. As for the protection of public health, there are calls for ongoing cooperation between current EU–UK systems, for example, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control’s infectious diseases warnings.

Parastoo Karoon, principal consultant, regulatory, with the contract research organization Parexel, told Pharm Exec that, in preparing for a no-deal scenario, businesses “must establish an EU/EEA (European Economic Area) legal entity (to transfer UK licenses to); establish a qualified person (QP) release site and testing facilities in EU/EEA locations; and obtain new CE marking from an EU-registered body for their existing devices.” She adds that companies “would do well to stock-pile commercial and clinical trial supply in both regions, as well as establish a QP responsible for pharmacovigilance (QPPV) and transfer pharmacovigilance system master files to an EU/EEA location, while making substantial amendments to clinical trial applications for change-of-sponsor legal entity.”

Stockpiling is also being advocated by the UK government. In December, the government asked pharma companies to increase their rolling six-week stockpile of medicines to a six-month stockpile in the event of no deal. Following the announcement of May’s postponement of the Commons vote, Mike Thompson, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), gave an assurance that the industry’s focus “is on making sure that medicines and vaccines get to patients whatever the Brexit outcome” and that it is “working as closely as possible with government on ‘no-deal’ planning.”

Despite these contingency plans, however, the industry remains overwhelmingly opposed to a “no deal.” ABPI’s Thompson also emphasized that a no-deal Brexit would present serious challenges that “must be avoided.” He commented: “Politicians need to find a way through the current impasse and reassure patients that medicines will not be delayed or disrupted come March 2019.”

His comments were echoed by Nathalie Moll, director general of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), in her end-of-year blog on Dec. 13. Calling on the UK and EU to push for a deal that allows for “immediate and intense focus” on the regulation and supply of medicines in the post-Brexit relationship, Moll asserted that “explicit commitment to securing long-term, extensive cooperation around the regulation of medicines and medical technologies is in the best interests of patients and public health.” She added: “This has to be priority in 2019.”

- Julian Upton

Pharma’s Digital Dive

Wading the digital therapeutic waters

Will 2019 be the year that the pharmaceutical industry figures out how digital health fits into its business-and makes a giant leap into the space? It’s uncertain, but, whatever the result, it likely won’t be from a lack of trying to navigate the shifting terrain.

In fact, experts who spoke with Pharm Execsaid that digital health has become such a top priority in their organizations that some planned to split their time between the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco and the Digital Health Conference at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, both of which took place the same week in early January. The experts said they are using the time at CES to not only meet with digital leaders who excel in consumer healthcare, but also to learn more about how consumers, or patients, are using digital products.

During a number of roundtable discussions at CBI’s Digital Therapeutics Conference in New York City last month, executives agreed that digital health strategies at pharma companies are often still dictated by specific goals set by C-suite leaders. And just because they may declare digital health is a priority for their organization, it could mean anything from digitally updating the supply chain, to actually creating a digital therapeutic; the definitions and expectations of digital health vary greatly.

Defining the terms

As David Amor, vice president, quality and regulatory affairs at Pear Therapeutics, asked at the start of his presentation during the CBI conference, “what the hell is a digital therapeutic?” Although it may seem like a simple question, the fact of the matter is that it can be more complicated than one might think.

According to the Digital Therapeutics Alliance (DTA), a non-profit trade association founded in 2017, digital therapeutics are defined as delivering evidence-based therapeutic interventions to patients that are driven by high-quality software programs to prevent, manage, or treat a medical disorder or disease. They are used independently or in concert with medications, devices, or other therapies to optimize patient care and health outcomes.

It’s clear that this definition is not the same as the product a traditional pharma company is used to making. In fact, as Amor explained, in many cases, according to government regulations, these treatments fall into the medical device category. “Digital therapeutics, for the most part, are treated as medical devices,” he said. “What does that mean? Is there a chemical reaction? No. So, that’s why it’s stated as a medical device.”

In other words, drugmakers who are looking to create, purchase, or partner with a company around a digital therapy, are now entering an area, including the related FDA regulations, that they may not be traditionally familiar with: medical devices.

Determining the outcomes

Stepping into this new space, experts say, means that pharma companies will need talent with a different skills set than they would normally be looking for when recruiting new hires.

As a result, the industry, experts believe, will start to see more forward-thinking pharma manufacturers bringing in employees who have medical device experience as well as programmers from top tech companies to join their ranks. But speakers at the CBI conference said that someday in the near future, they hope to see college graduates who would typically head to the Silicon Valley, instead choose the pharma corridor.

“Digital therapeutics as a sector will become sexy enough that they will want to work in digital therapeutics, and not wonder why they would want to work for a drug company,” said David Keene, chief technology officer at Dthera Sciences, during a panel discussion.

Challenges ahead

In addition to the hurdles mentioned, one of the main challenges-and perhaps biggest-facing pharma companies in the coming year around digital therapeutics is revenue. As David Klein, co-founder, chairman, and CEO of Click Therapeutics, pointed out at the conference, despite there being hundreds of thousands of

digital health apps available, with more being added everyday, no one is “deriving significant revenue in that space.”

“If you need FDA clearance, the bar is set pretty high,” said Klein. “There is a misperception that an app can pivot on a dime, and we are going to get FDA clearance-it’s not that simple.”

Despite the fact no one has solved the “business-model” problem when it comes to digital therapeutics or digital health apps, it doesn’t mean companies aren’t going to keep trying. In fact, Klein said that over the next six months, expect to see some “significant transactions that will serve as catalysts,” as the industry gains more startups and investments in the digital therapeutics space.

“We have just seen the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Expect to see a significant shift in capital, partnerships, and reimbursements.”

- Michelle Maskaly

Cell and Gene Therapy Check-in 2024

January 18th 2024Fran Gregory, VP of Emerging Therapies, Cardinal Health discusses her career, how both CAR-T therapies and personalization have been gaining momentum and what kind of progress we expect to see from them, some of the biggest hurdles facing their section of the industry, the importance of patient advocacy and so much more.