Being Fred Hassan

Pharmaceutical Executive

The Schering-Plough story offers a fascinating tale of a turnaround. But it's also a story of how a leader can right the ship of the beleaguered modern-day pharma company. Given the challenges the industry faces, models of effective leadership are precious. Who can today's execs learn from? To some extent or other, many leaders need to set themselves to the task of studying, emulating, and being a leader like Fred Hassan.

Sometimes you can spot a train wreck before it happens. At that point, the only thing that matters is who's driving that train.

Take Schering-Plough. In the 1990s, it was big and profitable, thanks to Claritin (loratadine), the allergy drug that almost single-handedly introduced the DTC era. At its peak in 2001, Claritin generated $3.1 billion in sales—almost a third of SP's total revenues.

Then the bubble burst. Faced with generic competition, SP's sales plummeted by more than 70 percent. SP's hepatitis franchise, with stiff competition and a product that eliminated demand by curing patients, dropped as well. Schering was leaking cash to the tune of $1 billion per year. What's more, the company was dealing with a multitude of regulatory issues, from FDA fines to a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation to charges of improper marketing.

Who you gonna call?

Well, how about a man who has already been CEO of two major pharmas, who's cowboyed the biggest turnarounds, and who practically created the modern pharma mega-merger? A guy who goes from company to company with an entourage of loyal and experienced execs, keeps a firm rein on the ad agencies, gets out and mingles with the district managers, and commands such respect that "Fred says" is an almost surefire way to win an argument in a company he leads.

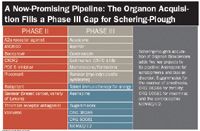

A Now-Promising Pipeline: The Organon Acquisition Fills a Phase III Gap for Schering-Plough

In short, how about Fred Hassan?

Schering-Plough made the call, and Hassan took over in April 2003, dressed in his uniform of grey suit, white shirt, and red tie. He came armed with a five-step turnaround plan: stabilize the company; repair it; turn it around; build the base; and break out. Estimated time to completion: six to eight years.

But first, inform the employees. Within the first few days of arriving at SP, Fred did a road show of his plan. "In hindsight, that was the right thing to do," says Hassan. "It gave the whole company a road map to work with, a sense that there was somebody in charge even as they knew they were facing very difficult problems. At that stage, the best you can do is show that you are in charge and in control."

Hassan immediately cut expenses. (Good-bye company jets, cafeteria, and half-day summer Fridays.) He froze salary increases and bonuses (even his own) and cut dividends by 68 percent, drawing gasps from investors, who had seen the dividend rise 17 times between 1986 and 2000. The stock tumbled.

Long-Term Shareholder Value

Hassan, meanwhile, was rebuilding. Key to the plan was Vytorin, the cholesterol drug that combined SP's Zetia (ezetimibe) and Merck's Zocor (simvastatin). Hassan worked closely with R&D head Thomas Koestler on the evolving label. SP needed Vytorin to save the company, so everything had to be perfect. Hassan remembers the drug's launch meeting. "It was a very emotional gathering," he says. "It was not just a product launch, it was the re-launch of a company."

And sure enough, since the Vytorin launch, SP has

• had 11 straight quarters of double-digit growth

• is the fastest-growing company in its peer group

• is well positioned for future growth, especially with the acquisition of Organon BioSciences, a deal that is expected to close by the end of 2007.

The Schering-Plough story offers a fascinating tale of a turnaround. But it's also a story of how a leader can right the ship of the beleaguered modern-day pharmaceutical company. Given the challenges the industry faces, models of effective leadership are precious. Who can today's pharm execs learn from? To some extent or other, many leaders need to set themselves to the task of studying, emulating, and being a leader like Fred Hassan.

Which leads to the real question: How does he do it?

1 Start Early

Hassan was born in 1945, and he gives part of the credit for his career to lessons he learned while growing up in Pakistan. From his father, the country's first ambassador to India, he learned about war, diplomacy, and bridging cultures. His mother, a women's-rights advocate (no easy role in an Islamic country), taught him to take risks and to decide for himself what's right. In school, he loved geography and picked up English from Elvis.

Hassan left Pakistan to study chemical engineering at the University of London, then business at Harvard. When he graduated in 1972, he joined Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, working his way up the ladder with risky, difficult assignments: the reorganization of a marketing unit in Nebraska; then the turnaround of Sandoz's failing local operations in Pakistan.

"These jobs got me to see new things and tested me in different environments," says Hassan. "This is one of the industry's big challenges. By the time people are in the situation where they wish they had more exposure, it's hard to rotate out because they are very senior in a functional role."

By the age of 42, Hassan was CEO, a job he held until Sandoz merged with Ciba-Geigy in the $30 billion deal that created Novartis, the world's second-largest drug company. He moved to American Home Products and became president of its Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories division. Before long, Hassan was elected to AHP's board of directors and eyed as heir apparent to CEO John Stafford.

But a much greater opportunity (read: challenge) awaited him. In 1997, he became CEO of the newly formed Pharmacia & Upjohn. The company had realized some savings from the merger, but it was failing to meet postmerger targets. To Hassan, job one was to untangle the mess created by the original merger plan, which gave operational autonomy to the company's business units in Kalamazoo, Stockholm, and Milan. To break down the cultural divides that split the company, Hassan picked five products for the entire team to unite behind. Then he moved P&U to New Jersey, where Hassan has lived ever since.

In 1999, Hassan engineered another mega-merger, this time with Monsanto, for $37 billion, gaining control of arthritis drug Celebrex. But that deal was dwarfed by what came next: the 2002 merger of Pharmacia and Pfizer, which created the world's largest drugmaker—by far.

The deal was pharma's biggest ever, but in terms of challenge, the high point was yet to come—on Hassan's second day on the job at Schering-Plough, he had to persuade an angry board of directors to buy into his action plan.

How did Hassan know what to do? "When you're in a turbulent situation, you have to take charge and work with imperfect information in a very limited period of time," he says. "That's where it really does help to have faced a similar pattern of problems in the past.

2 Make 'em Trust You

A pharma leader is responsible for engendering many forms of trust: from shareholders ("I believe in what you're doing for the company"); employees ("I like working here, and I believe I have a future"); and customers ("Your company's products can help me/my patient").

When Hassan came to Schering-Plough, customer trust had deteriorated beyond recognition. Reps' competitive bonus structure was one of the underlying issues—it created a hard-sell environment, with reps chasing the sale today instead of the relationship tomorrow.

Hassan set about organizing for long-term value. He changed the salary/bonus split from 60/40 to 80/20, to be more in line with the industry standard. At the annual sales force meeting, Hassan stood before the reps to talk about trust, concluding with what would become an iconic moment: He told them that if they had to choose between doing what's right and making a sale, to walk away from the sale.

The reps, many of whom stood to lose money by heeding Hassan's words, gave the CEO a standing ovation. Soon the sentiment echoed throughout the company.

"The whole thing is about values, a sense of destination, a sense of direction for the company," says Hassan. "That's a very powerful method of getting productivity. In particular, if the district managers connect with you, then they know what you're trying to do and will be on your side, instead of feeling like you are some distant corporate suit."

SP's president of global pharmaceuticals, Carrie Cox, agrees: "In the early days, people weren't sure if these words were a corporate slogan. Fred took the concept from what could have been rhetoric to something that people could live and understand and embrace."

3 Invest in the Long-Term

Pharma currently suffers from "short-termism"—the failure to attend to long-term, sustainable results. Hassan blames the focus that management puts on quarterly numbers. "Even though they all would like to believe that it doesn't create pressure, the reality is it does," he says. "And if you're chasing quarterly numbers, you may not be paying attention to what's right for the business."

When Hassan got to Schering, he felt he couldn't issue reliable short-term guidance to Wall Street, so dependent was the company on its Zetia joint-venture partner, Merck. As time went on and SP found its feet again, Hassan realized that he no longer wanted to provide short-term guidance. Without it, he was freer to do the right things for the business.

How did Hassan manage to skate the Street without getting slaughtered? In some ways, it seems to be all about respect. "Fred has enough credibility with investors where he can say, 'I don't need to be micromanaged by you guys,'" says Daniel Teper, who worked for Hassan at Sandoz, and now is the North American managing director of the Bionest Partners.

"The Street likes more transparency, not less," says Les Fundleyder, a healthcare strategist for Miller Tabak. "But Fred does what he says he is going to do. When someone executes according to plan, that makes the Street happy. Now, more companies are moving toward the Schering approach and moving away from quarterly numbers."

4 R&D is the CEO's Job

To Hassan, lack of pipeline productivity—by no means limited to SP—is a failure of leadership. "You can't rely on these large products to keep you going forever," he says. "I'm not sure if too many CEOs understand or internalize that. They hope that the head of R&D will get the job done—that they'll get, say, $2 billion in new products each year. But that's the central function of the business."

When Hassan got to SP, he increased the R&D spend. But it was going to take more than R&D dollars to overcome the decade-old pipeline gap and neglect of the research infrastructure. Hassan went shopping, focusing on the Phase III pipeline. He licensed prostate cancer drug Asentar from Novacea and acadesine, for preventing ischemia-reperfusion injury, from PeriCor.

Most notably, Hassan led the acquisition of Akzo Nobel's Organon BioSciences, with five Phase III projects, which nearly doubled SP's pipeline. The purchase also brought in research expertise in CNS, women's health, and anesthesia. A bonus: Organon's new, state-of-the-art, GMP-certified, biological manufacturing plant—a timely fit for SP, which is now moving its first biotech candidates into human testing.

And SP's R&D engine is starting to kick in. It has four fast-track projects in Phase II: a thrombin receptor antagonist, which is being tested for the treatment and prevention of cardiac events in patients with acute coronary syndrome; vicriviroc, an HIV drug that is a CCR5 receptor antagonist (as a first-line treatment, the results proved disappointing, but Tom Koestler still believes this will be "a best-in-class molecule"); the protease inhibitor boceprevir, and the A2a receptor antagonist for Parkinson's disease.

The deals have helped fill the pipeline gap, but Hassan says that, in the long run, the company needs to have its own competence at developing new drugs. "If someone else does the R&D for you, they could also do the marketing," he says. "Why would they need you?"

5 Like Your Job

In the dog-eat-dog world of pharma M&A, you have to marvel at Hassan's elegant positioning of Schering-Plough to acquire Organon. Wall Street had been after him for years, speculating about targets, pinning SP as ripe for a takeover. Finally, four years after getting behind the wheel at the company, Hassan made his move.

At first, many called the $14.4 billion price too high—but that chatter has mostly ceased. Aside from the promise of Organon's Phase III pipeline and the reduction in costs due to synergies, most analysts think Hassan can easily revive Organon's core contraceptives and fertility businesses, given his role in building Wyeth's women's health business.

Ask Hassan how he landed the deal, and he'll credit it to something simple: He likes his job. "If you are interested in your job and really interested in your business, you remain in tune," he says. "If you are in tune with the business, then you are able to move quickly when opportunities open up."

Hassan had closely followed Organon and Akzo Nobel, Organon's parent company, over the years. At one point, the companies were even codeveloping a male contraceptive. Hassan said he could see change brewing. For years, Akzo had tried unsuccessfully to boost the profits of its pharma division. In September 2006, the company announced it would concentrate on its chemical and paint businesses and separate out the pharma business. But two months later came the death blow: Pfizer walked away from a codevelopment deal on asenapine, a treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

"We thought that was a good opportunity to present an offer that would be better than what they would get for the partial IPO price," says Hassan. "The fact that we knew about this asset, had followed it for a long time, made it much easier to move with confidence when the opportunity opened up."

6 Be a Market Shapeshifter

Have an unflinching focus on the consumer—it's a mantra that Hassan lives by. "You have to trust your own instincts and do your own homework, especially when it's a new technology," he says. "In many ways, it's about how you create and shape a market and consumer demand, how you predict consumer behavior. It's impossible for conventional marketing research to give you a good answer."

Hassan's deep involvement with brands has earned him a rep on Madison Avenue as a micromanager. He famously caused a three-month delay in the consumer campaign for Pharmacia's Detrol (tolterodine) by constantly reviewing and even rewriting ad copy. At SP, he sits in on every brand review.

Still, he's a master of execution. And in the end, that's what marketing comes down to. Some case studies:

A drug can make a market In 1983, Sandoz launched the transplantation drug Sandimmune (cyclosporine). The analysts thought it had a tiny market. Hassan thought it was a blockbuster. He proved right. He realized the number was low because the organ rejection rate was high: "You can expand markets," he says. "Once you have a valuable tool, usage in the disease goes up dramatically."

Pharmacoeconomics makes sense anywhere In the early 1990s, as executive vice president of American Home Products, Hassan was told that European price points would not go past a certain level for the rheumatoid arthritis drug Enbrel (etanercept). Hassan proved them wrong: He showed regulators the value of the product—specifically, its potency and specificity—and now Wyeth sells Enbrel at about the same price in Europe as it does in the United States.

Good DTC works As head of P&U, Hassan saw the ability to reposition the incontinence drug Detrusitol (tolterodine), then seen as a niche drug, as Detrol, a drug for "overactive bladder." "If it's something that's a little closer to the human experience, then you don't mind bringing the subject up with a doctor," says Hassan.

He saw Detrol as a growth engine and put sales and marketing muscle behind it—even as P&U was still smarting. With expanded resources, the company took Detrol not just to urologists, but to primary care physicians and consumers to create a mass-market drug.

Grow in the face of generic competition Even with Merck taking half the profits on the joint venture that markets Zetia and Vytorin, the cholesterol franchise is Schering-Plough's company's largest, bringing in nearly $2 billion for the company in 2006. For the first six months of 2007, sales were tracking 38 percent ahead of 2006.

What's more, Vytorin and Zetia are the only major brands in the crowded cholesterol-lowering category that have gained market share in total prescriptions since the end of 2006, according to the company. In this way, Schering-Plough has been effective at getting the message through to docs: Simvastatin alone does not get patients to their goal.

Still, challenges lie ahead. Major questions surround asenapine, given the mixed Phase III results that drove Pfizer off. But Hassan has experience in the market: At Sandoz, he championed the schizophrenia drug Clozaril (clozapine), which came with a risky side-effect profile. For asenapine, Hassan says the safety and efficacy studies are there and pays no mind to naysayers.

"Many drugs don't look very good at certain stages in their journeys, and many drugs fail in the end," says Hassan. "That's the way our business works. But I can tell you this: Almost every successful drug went through periods in its journey when it was a candidate for discontinuance."

Still, by the time asenapine gets to market (if it does), Clozaril and others will have lost patent protection. That means good results won't be enough—asenapine needs great results. The opportunity: Phase II data show asenapine helps patients' "negative" symptoms—lack of interest in themselves, their environment, etc.—a deeply unsatisfied need.

7 Have a posse

Hassan has not been shy about bringing his inner circle with him. He's worked with Carrie Cox, and others, since his days at Sandoz. And since joining Shering-Plough, he has replaced almost the entire executive management team with people he worked with at Pharmacia. First came Cox as head of the global pharmaceutical business. Next were Bruce Reid (who has since died) and Ken Banta, as head of strategic communications, respectively. R&D director Tom Koestler; senior vice president of global licensing Michael DuBois, and others followed, until the team was complete.

Some have been critical of this approach—saying SP was taken over by Fred Hassan, Inc. Hassan, however, makes no apologies: "When it's important, and you're in a hurry, you go with someone you can rely on."

8 Diversify

Which is better: a pure-play pharmaceutical company or a diversified company? After a career at the likes of Sandoz, Wyeth, and Pharmacia, Hassan's point of view is hardly surprising. Shering-Plough has maintained its OTC business, with brands including Dr. Scholl's and—since its patent expired—Claritin. With the acquisition of Intervet, Organon's animal-health business, SP will become a leading animal-healthcare company.

The point, says Hassan, is to get maximum value from the molecule. Claritin OTC, for example, had sales of nearly $400 million in 2006. And Schering-Plough did the switch in-house—unlike, say, Roche, which had to partner with GlaxoSmithKline on Alli (orlistat), the OTC version of weight-loss drug Xenical. Research insight can be shared as well. For example, in developing Nuflor (florfenicol), an antibiotic for swine, Schering-Plough used the results of human research it had conducted. The importance of this sort of crossover cannot be overstated, especially when you consider diseases such avian flu, for which Intervet already supplies a vaccine for birds.

These are strong places for the company to be, and Hassan believes that market trends are on Shering-Plough's side. With increased regulatory scrutiny, more rigorous safety studies and postmarket research needed, means that, for the right drugs, there will be more OTC candidates. What's more, payers would like to see more drugs go OTC to lower their health tab.

9 Know Your Challenges

With profits that have moved from a billion in the red to a billion in the black, things are looking up at Schering-Plough. The Organon acquisition has pushed off the threat of a takeover, possibly by Merck with which SP partners on Zetia, Vytorin, and a new Singulair/Claritin combo pill awaiting FDA review. But Hassan, at age 62 and with a contract that runs through 2010, doesn't show any signs of slowing down.

The first order of business is to roll out the regulatory filings and launches for Phase III drugs. Then there's the integration to handle. There's an art to merger-induced organizational change—and as Cox puts it, "there's no person with more experience in the pharma industry than Fred." The integration is smaller than, say, combining Pharmacia and Pfizer. But in some ways, it may be more complicated. Since Organon's Intervet is larger than SP's animal-health business, there will need to be an element of backward integration, where SP's unit will be the one to change its systems.

Certainly, Hassan is making progress on his five-point plan. But the question remains: Is Organon enough?

The answer depends on what the company wants to be when it grows up. Hassan says he doesn't care if SP is a top-10 company, as long as it has top brands in its target markets. To get there will likely require more deals in oncology and CNS, in which the company has smart investments but would benefit from a franchise approach.

Others say that additional investments are key to further diversify the company's reliance on its cholesterol franchise, which contributes 78 percent of its pretax profits, according to Bear Sterns. Even after the absorption of Organon, by 2010, that number will decrease only to 71 percent. Cox is careful to remind that the cholesterol market is an area of such large opportunity, and SP sees it there for the taking, particularly with the development of its Phase III thrombin receptor antagonist moving full-steam ahead.

Still, one gets the feeling that, despite these challenges, things at Schering-Plough are all right—and will be, as long as Fred Hassan is around. Hassan says the fact that "the industry is going through a dificult time shouldn't discourage us—it should just force us to change the way we do things." One would argue that Hassan doesn't have to touch a thing.

The Misinformation Maze: Navigating Public Health in the Digital Age

March 11th 2025Jennifer Butler, chief commercial officer of Pleio, discusses misinformation's threat to public health, where patients are turning for trustworthy health information, the industry's pivot to peer-to-patient strategies to educate patients, and more.

Navigating Distrust: Pharma in the Age of Social Media

February 18th 2025Ian Baer, Founder and CEO of Sooth, discusses how the growing distrust in social media will impact industry marketing strategies and the relationships between pharmaceutical companies and the patients they aim to serve. He also explains dark social, how to combat misinformation, closing the trust gap, and more.