2016 Brand of the Year: Cancer Standout Opdivo

Pharmaceutical Executive

Pharm Exec’s 10th annual Brand of the Year is Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Opdivo, which has raced into the lead position in the treatment-shifting immuno-oncology space behind launches in three key cancers-melanoma, lung, and renal.

Bold strategy has defined the year for Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Opdivo, boosting it into the lead position in the innovative immuno-oncology space. Launches in three key cancer arenas-melanoma, lung, and renal-have led to a unanimous selection for Pharm Exec’s Brand of the Year by our Editorial Advisory Board-and its run to clinical excellence may just be beginning.

Nearly 18 inches of snow blanketed Washington D.C.’s Reagan National Airport on the weekend of January 23. Weather watchers throughout the district saw depths as high as three feet, clogging government functions, airports and businesses for the week. Despite a region-wide government office closing, FDA staffers endured and industriously managed to pump out an extremely rare Saturday approval.

Usually when a PDUFA date, the deadline for the FDA to review a new drug, falls on a Saturday, the therapies are approved on the Friday before, but these were extenuating circumstances, explains Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Chris Boerner, head of the company’s US commercial operations. While the weather brought snowmen, hot cocoa and sledding to Capitol Hill, for BMS it was business as usual for an organization having a truly epic year; this was the seventh FDA approval for its immunotherapy Opdivo (nivolumab) since the first in advanced melanoma in December 2014, and the fourth for late-stage melanoma. BMS’s Princeton area offices were quieted by the squall Friday night into Saturday, leaving many employees homebound with their families. Some trudged through the white managing to make it in while others hunkered down with laptops and phones, conferencing in on demand to ensure they were available to handle the approval. Many others were holed up in far-flung hotels across the country, stranded by flight cancellations.

FDA’s declaration granted an expanded indication for an immuno-oncology (IO) combo salvo, Opdivo + Yervoy (ipilimumab), against advanced melanoma. Now patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma regardless of BRAF gene mutational status could be candidates for the dual treatment where BRAF V600 wild-type status had been a prerequisite, roughly doubling the patient pool for on-label treatment with the drug combo in metastatic melanoma.

More so, BMS claimed one more victory in distancing its IO leadership position. And as the call for combinatorial attack plans in oncology gets louder, BMS can claim an early lead with a combo that uses its pair of therapies. Meanwhile, as a plurality of combination ideas are conceived and planned, whether they use two IO drugs, or an IO therapy paired to a targeted cancer drug, a fair share are likely to run through BMS.

For launch team members, the blizzard was just another checkpoint and a minor inconvenience in an intense, emotional run that demanded solid planning, organization and passionate commitment. Schedules have been filled with positive data readouts, approvals and launches. “It’s been a roller coaster, launch followed by launch, and truly a once-in-a-lifetime career opportunity,” says Teresa Bitetti, head, US Oncology, BMS. She adds: “The commercial crew has been built upon a focus of getting innovation to patients, and emphasizing that patients should understand the new treatments options that are out there.”

“We have certainly exploded the travel budget,” laughs Emmanuel Blin, BMS’s head of worldwide commercialization. Seven approvals across three major oncology arenas, lung cancer, renal cancer and melanoma, proved an immense task for those on the commercial side, requiring a major investment and substantial planning. The audacity in planning such a launch could only be rivaled by the daring that it took to pursue so many indications along such a short timeline in the uncertain setting of clinical trials. Opdivo is batting a high percentage in these trials, and early data encouraged its medical leadership that their boldness was well founded. But for BMS, it was a confluence of factors, and overarching strategic realignment, that left the drugmaker prepared to pounce on the disruptive field of IO with a vision for answering unmet medical needs.

BMS oncology: Out of hibernation

The momentum carried by BMS’s PD-1 inhibitor Opdivo isn’t likely to let up any time soon. The company announced in January that it stopped its Phase III trial in head and neck cancer, CheckMate-141, early, on account of positive data demonstrating superior overall survival (OS) over the control arm, according to the study’s data monitoring committee. Overall survival data from this study showing benefit at one year was presented at the American Association for Cancer research in New Orleans in April. Head and neck cancer may see impressive growth in the next decade, with IO products a major driver to the market.

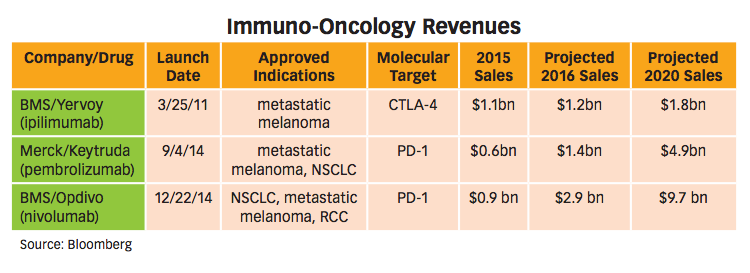

Stepping back to a view of the overall IO therapies market, including BMS’s Opdivo; Yervoy, its anti-CTLA-4 antibody; and Merck & Co.’s anti-PD-1 antibody Keytruda (pembrolizumab), the segment is projected for big numbers in the coming years. Analysts put annual peak sales for IO in the upper $30 billion range within the next decade. IO sales in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLS) alone project to around $10 billion yearly. Forecasters estimate 44% of the NSCLC market pie will go to BMS, while Merck will rein in close to a third of it. The time is ripe for companies to claim their positions in oncology, as IO therapies bring new promise and new profit potential.

Dating back to 1990, BMS might have been considered the leading oncology company. “Those were the Taxol days,” explains Fouad Namouni, head of medical for BMS. But for some time, big Pharma was not all that interested in

F. Namouni

oncology in terms of driving revenue. During the early 2000s, for about a decade, BMS remained a player but might not have been considered the “leader.” However, throughout this time, the company was building something-a mindset, a spirit, to conquer cancer, says Namouni. It was as if BMS was “hibernating,” waiting for the right time for a big move.

BMS jumped on this opportunity in oncology when it acquired Medarex for $2.4 billion in July 2009. Though the deal would bring BMS both Opdivo and Yervoy, as in all deals, it had its detractors, puzzled by the price tag and questions around the value of IO targets. Notably, Yervoy was seen as the crown jewel of the transaction, given that it had a surer timeline and approval in sight.

Bold moves backed by science

“We started talking to BMS on ipilimumab (Yervoy) as far back as 2000,” says Nils Lonberg, now senior vice president, Oncology Discovery Biology, for BMS, and formerly scientific director at Medarex. “We established an early relationship with BMS, taking a leading position in the new IO field. BMS made a substantial bet in 2009 before the Phase III data was known. This could only have happened with a good understanding of the basic science of IO.” Lonberg

N. Lonberg

adds that Medarex had shopped for additional buyers to no avail. “BMS was way ahead in thinking about IO when it decided to acquire Medarex. It continues to show its commitment to IO, with a focus that is integrated throughout the company.”

Lonberg’s postdoctoral work at Memorial Sloan Kettering, which eventually led him to GenPharm, bought by Medarex in 1997, was focused on the genetic engineering of mice. This work led to the development of a drug discovery platform that has had a key role in the discovery of an impressive who’s who of antibodies-nine of which are either approved or submitted therapeutics: golimumab, ustekinumab, ofatumumab, canakinumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, secukinumab, daratumumab, and bezlotoxumab. Medarex was involved in a substantial amount of partnering on this technology with many groups across the industry.

A key collaboration, initiated in 1998, that led to the discovery of Yervoy involved Lonberg’s team at Medarex together with Alan Korman at another biotech, Nexstar Pharmaceuticals (Korman joined Medarex in 2000, and is now vice president, IO discovery, at BMS), and Jim Allison at the University of California, Berkeley. Allison has since received plaudits (hinting at the likelihood of a Nobel Prize in his future) for his role in shaping this new vision in oncology treatment, and the partnership launched the Medarex team to the top of IO in its infancy.

The preclinical data was strong enough for a run in the clinic with Medarex beginning Phase I work on ipilimumab in mid-2000. The 2003 partnership with BMS fueled Medarex to persist until the buyout a half a decade later. “I was blown away by the commitment BMS gave,” says Lonberg, adding that it would have been difficult to persist in the long process of developing Opdivo over much of the decade.

“Training as a basic scientist is humbling. Not all ideas succeed, and it makes you have a real respect for nature-understanding its complexities and mysteries, and that you don’t understand it all,” Lonberg observes. “You grow up in the sciences with an almost Pavlovian response to data.”

It was with this data-thirsty mindset that Lonberg and his Medarex team stepped into the new field of IO. “There was so much new and exciting research coming from the interface of the immune system and cancer,”

Opdivo, like other immuno-oncology drugs, directs the immune system to engage cancer cells and prevent or slow their growth and spread in the body. (Getty Images/SCIEPR)

says Lonberg. The revolution in thinking of ways to approach cancer moved researchers from thinking about cellular mechanisms-how cells ultimately misbehave and become cancerous-toward thinking about how the immune system perceives these misbehaving cells. Of course, adding the immune system brings another layer of complexity, notes Lonberg. But the successes of IO therapies in the clinic, grasping some of this complexity, has been resounding in unleashing patients’ own immune systems to attack tumors.

Fortunately, combining Medarex and BMS was not overly complex. In addition to the ongoing partnership, scientists at BMS had discovered the ligand for CTLA4, “so there was a natural intellectual fit,” says Lonberg.

Though the IO field was in its infancy, thanks to this high level of intellectual familiarity, BMS brass had a grasp of the field’s potential. Management realized the asset they now were holding. Clinical development teams ramped into high gear.

“I was asked to lead, and in early 2011, we kicked off the development team,” says Namouni, who had seen early melanoma and renal cancer data and was impressed but not blown away. Other IO therapies were showing potential in these areas, so positive results were not earth shattering. But what Namouni saw as unprecedented-the lung cancer data; IO had yet to display substantial results in lung cancer, so if this could be confirmed, it could be transformational, he thought.

“We started the journey, and the way Opdivo was shrinking tumors, we knew we can impact survival,” says Namouni. He connected this real impact in survival for lung cancer to what he saw as BMS’s mission in its cancer comeback. “We made a connection to what we wanted to do to affect cancer survival, and we did it differently than most pharmaceuticals companies would have done. We did it in a bold way.” Investing at historic levels, an unheard of commitment, BMS set out after multiple tumor types condensed to an aggressively short timeframe. Given the scale of the effort, “we got looks throughout the industry,” says Namouni. “It was heresy to some degree to go for so many tumor types.”

The BMS teams were inspired by the approach. This hypothesis that putting pressure on the tumor over time will lead to OS was proving correct. And with that in mind, teams wanted to move quickly for patients. It was easy to justify the extensive investments into the numerous cancer types, notes Namouni.

The timing was perfect, too, for BMS’s leadership. BMS corporate strategy was transitioning from a diversified approach to one with a focus on areas of high need with the potential to bring transformational medicine. So the ingredients were there; the stars aligned to make that investment decision possible, explains Namouni.

Analysts had their questions regarding the approach, but company stock never suffered dramatically. Once people started seeing the data, critics were mostly quieted. Change is never easy, but the ingredients, culture and timing all came together for BMS to move forward with its bold approach. By 2016, Opdivo can almost taste entry into its fourth cancer type, and the aggressive trials have produced data that put the drug ahead of its competition.

BMS held a key advantage in developing its anti-PD-1, which helps explain the lead it has taken over Merck’s Keytruda. There is not yet a lot of data to make comparisons to Opdivo across indications in which it has provided solid survival data. But BMS added valuable experience from the development of Yervoy. “We learned a lot about trial design and doing clinical development in the IO space. That was a major advantage that helped us expedite Opdivo’s development,” says Namouni. BMS knew the optimal timing for peeking at data in an IO trial, for example, which gave the company a leg up, and other groups are still trying to figure out how to run their Phase III trials.

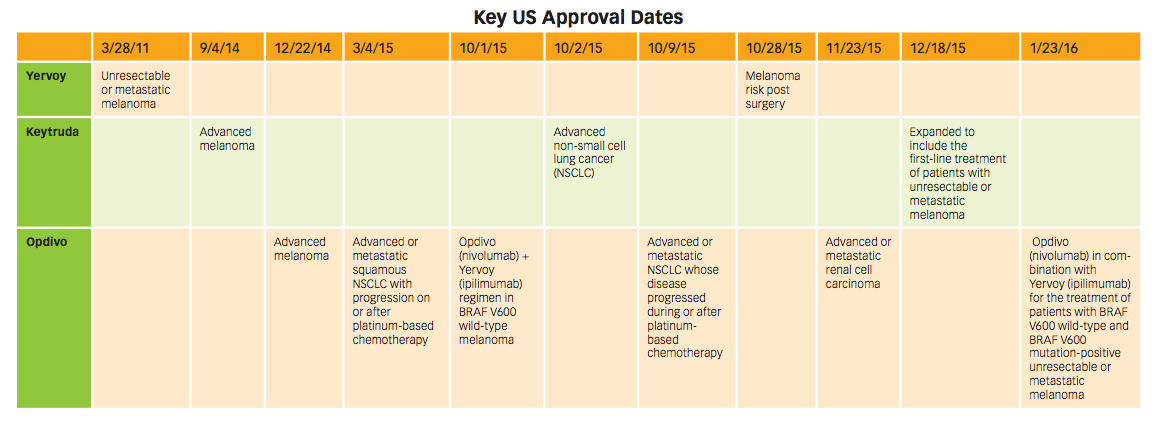

Keytruda beat Opdivo to the market in advanced melanoma, with approval in September 2014. Opdivo followed soon after in December of that year. But it was Opdivo’s first-place finish in advanced (metastatic) squamous NSCLC by six months that pushed it well ahead of Keytruda, and it hasn’t looked back.

Key indication approval dates in the US for Yervoy, Keytruda, and Opdivo. Click to enlarge.

Boldly impersonal

The industry’s emphasis on rare diseases, and the profits that can be found in these marginalized patient groups, carries a clear message into oncology. Where it’s evident that each patient is unique, individual tumors themselves can even be broken into sub, sub categories. A “Cancer Moonshot” mandate from the US’s chief executive branch with precision medicine terminology surely offers optimism that in the future, cancer treatment will be preceded by, and fitted to, in-depth diagnostics.

But Opdivo seems to have achieved its market thus far by discarding the shackles of personalized care and the complex diagnostics that come with it. What does it mean for the movement toward personalized medicine when the year’s biggest drug launched more quickly, and to larger pools of patients by making its personalizing diagnostic tests a companion, but not a requirement for treatment?

“Opdivo has been a game-changer,” says Dr. Jeffrey Schneider of Winthrop-University Hospital’s Long Island Cancer Center, who treats lung cancer patients. Schneider says that as many as 20% of metastatic lung cancer patients, who would have been given little more than survival timelines in increments of six months, a year, etc., can now see meaningful responses and real survival with no known expiration date. He adds that though one in five see this response, the drug offers hope for five out of five. Before Opdivo, there was such a “defeatist” mindset. In time, the remaining 80% will have other options rather than losing time and money on failing with a single IO therapy.

Patients in the future will have better diagnostics that point them to another treatment, or an ideal combination of drugs. Part of the predictive diagnosis will likely include the presence of ligand PD-L1, which Merck included in Keytruda’s trials as an enrollment condition, and as a result landed on its label. BMS also ran the trial looking at PD-L1, but didn’t use it as a criterion.

The PD-L1 test does predict response, but not perfectly, explains Schneider. Roughly 44% of patients who test positive for the test respond well to Opdivo, but about 5% of PD-L1 negative patients still see a response. With no additional tests to predict response, Schneider sees it as clearly worth it to treat these patients who are negative for the ligand. Payers, patients and regulators are also in line with the 5% gambit, given the hope of prolonged survival.

European two-step

The aggressive launch strategy has not been limited to the US. Opdivo is approved in over 50 countries, with reimbursement in at least one indication in each, according to Blin. BMS is seeing Opdivo attain similar levels of uptake and dominant market share across regions. The quality of the product is clearly first and foremost, but Blin also credits commercial strategies. “It’s a very competitive market, so it’s about not being complacent and remaining on our toes,” he says.

BMS decided on a unique commercial model for its global strategy that has been key in its rapid execution of commercial strategy across markets. “In most companies, you do the job twice-building a global strategy, then again for each

E. Blin

local market,” says Blin. Because the company stressed speed to market, BMS strategized around regional market blueprints to be executed in each country rather than planning for each individually. “With new indications coming online at a rapid pace, we can’t spend time aligning behind each one.”

In terms of access, companies typically negotiate for weeks and months in each country level to decide on local reimbursement. For Opdivo, BMS “reverse engineered” the process prior to approval, building in bookend values that consistently brought results. The company has been able to bring organizational speed, mobilizing with the mindset that “patients can’t wait.” Blin adds, “As a commercial person, you don’t have the opportunity to launch a drug like this very often. When we started to see the speed FDA was willing to move at, the speed at which doctors were willing to prescribe, it became evident that we had something unusual. We had to build a commercial model fit to purpose. It’s a heavy investment but worth it when you believe you have something transformational.”

“In the spirit of speed to patients, we knew that there is no regulatory way in Europe to have multiple indications submitted and approved at the same time,” says Namouni. It’s a sequential process whereby a marketing authorization application (MAA) is followed by a type-II variation and so on. In collaboration with the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), BMS came to Europe with a strategy that was unique and perhaps an innovation in itself.

The company strategized to use parallel submissions using different trade names, Opdivo and nivolumab MAAs for advanced melanoma and squamous NSCLC, respectively. EMA okayed the plan to “reconcile” the MAAs into a single marketing authorization under the trade name Opdivo toward the end 2015, “in order to accelerate availability of nivolumab for healthcare professionals in both indications,” stated a July 2015 press release.

Awareness and access

American consumers faced, and may have had difficulty avoiding, the boldness of BMS’s reported $42 million DTC campaign. As DTC inspires those across the spectrum, critics came forward with valid concerns that the “wide optimism” and a somewhat vague message that patients might “significantly increases the chance of living longer” might have negative effects. And, of course, with greater exposure comes more voices hitting notes on the drug pricing debate, sure to call outOpdivo’s more than $100,000-a-year price tag.

“Diagnosis for the worst-off lung cancer patients basically has meant a referral to palliative care,” notes Bitetti. “There has been nothing new for years, so there was a nihilistic attitude in the doctor and patient communities.”

“The decision to do DTC in this space was not taken lightly,” adds Boerner. But BMS executives were quick to point to lung cancer as a truly unique situation. “Twenty-five to 35% of patients with advanced lung cancer are out of the treatment algorithm,” says Boerner. “So as much as anything, DTC was an effort to reach them.” BMS went down the DTC avenue because the company thought it was a “public health issue,” according to Blin.

DTC marketing and the widely reported news of former President Jimmy Carter’s successfully treatment for metastatic melanoma with Keytruda have certainly raised awareness, added Dr. David Spigel, chief scientific officer and director, lung cancer research program, at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

Lung cancer is a disease area that has not seen data improving OS in many years. Thus the level of DTC investment makes sense, says Boerner. “There are critics who will always be negative on DTC, but patient advocacy groups were among those pushing us to do DTC and raise awareness.”

The price of boldness

The commitment to patient support and access to Opdivo is first in class, says Boener, noting the clear proof of this has been the positive reaction of payers. This is especially notable given the high list price tag for Opdivo and the environment over the last few years in which payers have been more than willing to wield influence, competition and the media against drugmakers.

But oncology products are rather protected from the price debate because of the emotional quotient (EQ) involved in treating cancer, according to Roger Longman, CEO of Real Endpoints, a start-up focused on pharmaceutical reimbursement. Because of the EQ, payers feel that they have very little freedom to restrict use of these drugs. This could be changing, Longman believes.

Opdivo is certainly worthy of Brand of the Year praise, but unlike Humira, which might have gained Brand of the Decade status, anything that is true today is unlikely to be true tomorrow, suggests Longman. There will be competitors, and payers will look hard to competitors for superior value offerings. In a reference to tools such as DrugAbacus.org, which Real Endpoints constructed with Dr. Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering, value measures and objective tools will become increasingly important for payers. Given other IO drugs coming to the market, non-IO agents, and the plurality of combinations that may be possible in the near future, there will be choices, and payers will be structuring ways of making decisions in a very complex market place, says Longman.

In a year that saw some pretty unimpressive launches (see the PCSK9 launches), “we’re seeing that pharma has failed to recognize and make adjustments to see value, not from their internal angle, but from the external vantage point in a world dominated by institutional buyers,” explains Longman. Oncology launches remain impressive but given the greater competition, and the dilemmas around combos, the ability for cancer drugs to launch so impressively may change, too. Oncology could see greater impact from payers’ ability to manage out high prices, adds Longman.

In regards to paying for innovation, BMS’s Namouni stresses that considering the impressive survival results showcased by Opdivo publications, it must be recognized that oncology treatment is witnessing a revolution. “Just look at the number of NEJM articles for Opdivo. Not everyone realizes the impact this drug and other IO agents will have for cancer treatment. This creates great value for society and the overall economy.”

For Dr. Spigel, a heartening moment occurred when one patient commented that his waiting room didn’t seem to be full of sick people anymore due in part to the effectiveness and fewer side effects with immunotherapies compared to traditional cancer drugs. Years ago, those awaiting treatment were in serious, and frequent, need of fluids and assistance. The perceived difference, Spigel notes, is telling for both outcomes and the outlook at the clinic.

“Valuing this kind of innovation is the right thing to do, because we need more innovation,” says Namouni. “The journey is not finished.”

Casey McDonald is Pharm Exec’s Senior Editor. He can be reached at casey.mcdonald@ubm.com

The Misinformation Maze: Navigating Public Health in the Digital Age

March 11th 2025Jennifer Butler, chief commercial officer of Pleio, discusses misinformation's threat to public health, where patients are turning for trustworthy health information, the industry's pivot to peer-to-patient strategies to educate patients, and more.