Direct to Consumer: If These Walls Had Ears

Pharmaceutical Executive

Dtc advertising has caused more than its share of controversy both inside and outside the industry. Critics wonder: Are patients paying for drugs they don't need? Meanwhile, industry is still struggling to answer the basics: How effective is DTC in getting patients to request a drug by name? CommonHealth's MBS/Vox division conducted a survey that tried to answer industry's question, and in doing so, inform the wider debate about DTC's role in healthcare.

Dtc advertising has caused more than its share of controversy both inside and outside the industry. Critics wonder: Are patients paying for drugs they don't need? Meanwhile, industry is still struggling to answer the basics: How effective is DTC in getting patients to request a drug by name? CommonHealth's MBS/Vox division conducted a survey that tried to answer industry's question, and in doing so, inform the wider debate about DTC's role in healthcare.

Joe Gattuso is president of CommonHealthâÂÂs MBS/Vox division and director of strategic insight and account planning.

MBS/Vox peered behind the doors of 172 health providers and studied their conversations with 440 patients. The study sought to determine how often discussions about prescription brands were taking place, and to uncover the correlation between DTC spend and risk–benefit conversations. The study focused on three segments—cholesterol, allergy, and hypertension. These three categories receive different levels of DTC spending (allergy and cholesterol spending is significantly higher than hypertension).

Meg Columbia-Walsh is managing partner and president of consumer and e-business at CommonHealth.

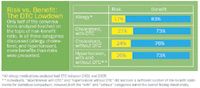

Of the analyzed visits, 291 included mentions of an allergy, cholesterol, or hypertension medication. Of those visits, only 17 references to DTC were made, eight direct (referred to actual ad) and nine indirect. The study found that more than half of the visits in which a medication was discussed included no mention of the risks or benefits of that drug. Of the visits where a risk–benefit discussion took place, more benefits than risks were presented in all three disease categories.

Crunching Numbers

Pharm Exec talked with Joseph Gattuso, president of CommonHealth's MBS/Vox division and director of strategic insight and account planning, and Meg Columbia-Walsh, managing partner and president of consumer and e-business at CommonHealth, to shed light on DTC's place in the patient–physician relationship.

Pharm Exec: What drove your company to conduct this study?

GATTUSO: We know how DTC works. When you study it, the ROI is there. But exactly what happens in the doctor's office that makes it work? We call it "the moment of truth"—when the physician and the patient are talking about therapy and a diagnosis. There's a lot of studies as to whether DTC marketing drives patients to the office, or if it raises awareness. We know that it raises awareness. We know that people are more aware of both the medications and the conditions when there's DTC. But what we decided to look at was the actual dialogue itself.

Risk vs. Benefit: The DTC Lowdown

COLUMBIA-WALSH: I've been in the industry for 20 years, and I've seen a severe pendulum swing, from 100 percent talking to physicians to an almost consumer-product-goods approach to marketing. Now we're seeing a pull-back, and I think that the place it's going to land is with the physician–patient dialogue.

This study is not secondarily reported [information], where you're asking somebody their opinion or asking somebody [about their experience] post visit. This is linguistically analyzed conversation.

Describe a typical conversation.

COLUMBIA-WALSH: In one conversation, the physician talks to a female patient almost in the form of a medical questionnaire—which is how they're trained. They ask very close-ended questions, such as, "When you get pain, does it do this?" "Yes." "Does it interrupt this?" "Yes." At the end of it, the patient walked away with an over-the-counter recommendation.

In the post interview with the patient, the interviewer asked, "How does this migraine affect your life?" It was like opening up the floodgates. You heard things like, "I can't go to work. I can't take my children to school. I'm disabled in talking to my spouse and he gets frustrated." When you hear about all of the interruptions to everyday life, and how severely they affected the patient's life, [you realize that a doctor's visit involving this kind of conversation] would have a different outcome.

How do we train physicians to ask, in the same amount of time, these types of questions—and [in ways that get the] patient to feel they have the empowerment to share that [information] without being rushed? It's not just a medical conversation, it's how the illness is affecting their life.

GATTUSO: A lot of times, rather than saying, "Ask your doctor about this brand," an ad can simply say, "Tell your doctor about the impact of this condition on your life." That will lead to the right kind of discussion and the right kind of medication. [Companies] need to repair some of the things in the dialogue that people say out of habit.

So, is DTC advertising not working?

GATTUSO: Look at it from a marketing point of view. If you say, "If I invest X amount of dollars, do I get a return?" the answer in many successful campaigns is yes, it does move the needle in terms of brand prescribing.

We're simply saying that it doesn't appear that a high percentage of patients are going to the doctor and directly saying, "I saw X brand on TV and that's what I want." And a lot of the critics of DTC have suggested that that's the case.

Does DTC affect the conversations between patients and physicians about a drug's risk?

DTC does not appear to negatively impact the level of risk–benefit discussion. There's no appreciable difference when a DTC brand is prescribed in terms of the risks and benefits that the physician would typically talk about.

We looked at every single mention of every medication in those three categories, which covered about 98 percent of all prescriptions written in those disease areas. But the risk–benefit discussions wasn't the classic, "These are your risks of treatment, these are the benefits of treatment. These are the risks of non-treatment, these are the benefits of non-treatment." We were very generous in what we coded as a risk or a benefit— even with that, most mentions of medications simply didn't have a risk or a benefit associated with them.

In the disease categories where companies spent money on DTC [allergy and cholesterol], more of those conversations had some form of risk–benefit conversation compared with in hypertension, which had significantly less DTC spend. So you can say, at least directionally, that DTC is not removing the risk–benefit conversation. But in all those categories, the risk–benefit discussion could be made much more relevant, stronger, and richer through a more evolved form of DTC, where it's based on the understanding of the dynamics of the conversation.

What was the most surprising thing about the results of the study?

GATTUSO: I thought that we would probably find more direct requests for brands that were advertised. People often read the data quickly and say, "So you're saying that DTC doesn't work." That's not what we're saying—DTC does work. What we are saying is that it's probably not working exactly as people believe; and we're also saying that we have an opportunity to make it work more effectively for the patients taking therapies.

It shows we can improve the doctor– patient conversation in a more emotionally validating way, in a context that allows a patient to truly understand how a disease affects their lives.

How can pharma companies incorporate this information into their marketing strategies?

COLUMBIA-WALSH: Consumers are very empowered, but they're like first-year medical students—over-confident and under-qualified. And if part of the cure is improving the physician–patient dialogue, then I think our segmentation and targeting have to be based on both quantitative and qualitative goals. We really have to think about how messaging can be articulated in a way that is truly relevant and can bridge the gap between the physician and the patient.

Bradley Davidson, VP, account group director of MBS/Vox, contributed to this article.

The Misinformation Maze: Navigating Public Health in the Digital Age

March 11th 2025Jennifer Butler, chief commercial officer of Pleio, discusses misinformation's threat to public health, where patients are turning for trustworthy health information, the industry's pivot to peer-to-patient strategies to educate patients, and more.

Navigating Distrust: Pharma in the Age of Social Media

February 18th 2025Ian Baer, Founder and CEO of Sooth, discusses how the growing distrust in social media will impact industry marketing strategies and the relationships between pharmaceutical companies and the patients they aim to serve. He also explains dark social, how to combat misinformation, closing the trust gap, and more.