A new study looks at the movement of thought leaders and medical science liaisons from primarily marketing to other areas of the pharma company. Though the shift might be minor (7 percent since 2002), it might be a sign of things to come.

A new study looks at the movement of thought leaders and medical science liaisons from primarily marketing to other areas of the pharma company. Though the shift might be minor (7 percent since 2002), it might be a sign of things to come.

The US pharma market grew just 3.8 percent last year, according to IMS Health. The big loser: lipid regulators. The winners: Biologic response modulators and monoclonal antibodies.

A review of a pilot ePrescribing program reveals that if physicians are given the proper support, the technology can increase safer prescribing habits and boost compliance.

Roche has always gone its own way with biologics, deals, and new medicines. Now that the rest of industry has caught on, how can Roche stay ahead of its time?

A new study shows that while doctors aren't in a rush to stop prescribing Vytorin, they are considering it less often as a first-line treatment option.

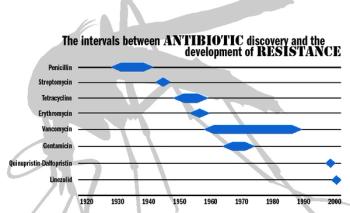

US officials think they can control MRSA and other "superbugs," but dangerous bacteria know no boundaries. What does the world do when its drugs stop working?

In the wake of the ENHANCE study, new prescriptions of the cholesterol-lowering drug Vytorin are dropping drastically, but calls to sales reps by physicians are on the rise.

Unlike Vioxx, Vytorin works exactly as explained in its now-famous food-and-family ads. So why are people up in arms against the drug? Experts ponder what went wrong.

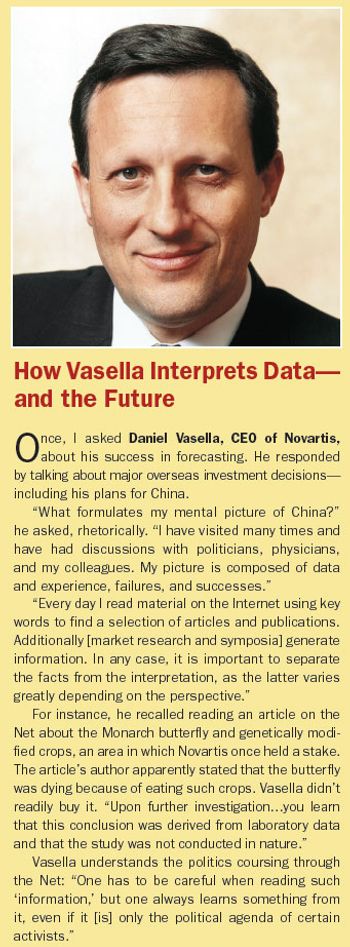

Managed care pharmacy executives list their favorite pharmaceutical companies based on promotional activities and the ability to meet managed care needs. Novartis reigns for 11th straight quarter.

Bright Spots Are Emerging Markets, Specialty Drugs, Says IMS Health

Business intelligence in a time of greater transparency is a whole new ball game. To play it well, be sure to look for surprising insights, expand your list of competitors of interest, and don't let Google be your only guide.

Novartis forced to cut 1,260 jobs due to dwindling pipeline, Zelnorm withdrawal. The company also adds new pharmaceutical division head.

Cancer R&D IS booming right now. At a time of poor ratings on both Wall Street and Main Street, pharma can at least point proudly to its oncology pipeline as proof that it still takes big risks to make big advances against big killers-and win. According to a recent IMS report, the cancer pipeline contains 380 compounds, with nearly 100 in Phase III. The long-established standard of care-surgery, radiotherapy, and chemo-is fast giving way to a high-tech array of targeted therapies. These molecules and antibodies are designed to block specific disease pathways, and they are proving both far more effective and far more tolerable than the sledgehammer status quo. Since 1996, the overall survival rate for patients has jumped by 30 percent, from one-half to two-thirds.

The clinical trials space these days is an alphabet soup of technologies: CTMS (clinical trial management systems); CDM (clinical data management); CDR (clinical data repositories); eCTD (electronic common technical document); and many more. But the technology with the most promise for transforming the way clinical trials are performed (and for driving everyone mad throughout implementation) is EDC-electronic data capture. It's taken more than a decade, but today most big pharma companies-and a fair number of smaller ones-are using some form of EDC in clinical trials. The early adopters might have experienced some growing pains, but the benefits seem to be outweighing the high cost of implementation. Few companies would consider going back to paper-based trials.

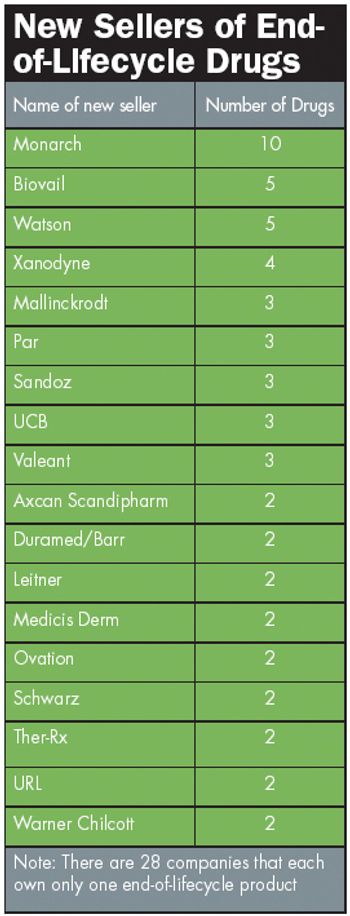

Very few drugs live forever. Barring remarkable scientific advances and radical market dynamics, most drugs hit old age-and sharply declining sales-several years before their patent expires. But some drugs go out with a bang, not a whimper.

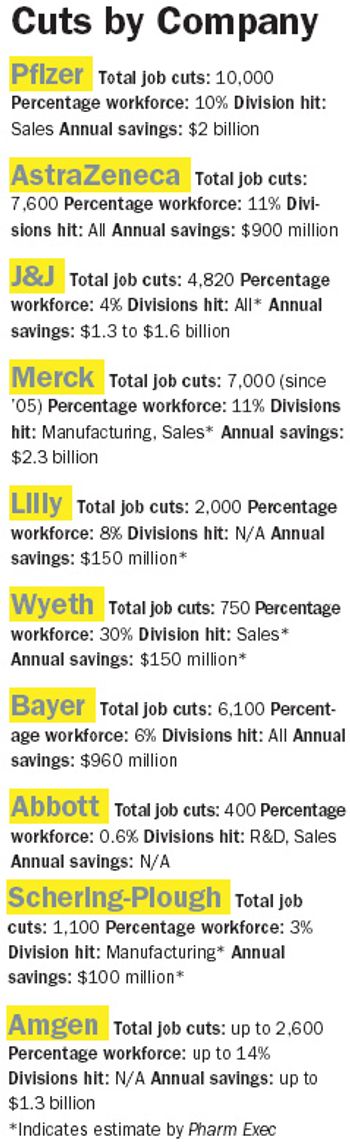

Ever since Jeffrey Kindler rocked our world last December with the news that Pfizer was cutting its sales force by 10,000, we've been waiting for all the other behemoths' shoes to drop. While no precise domino effect has occurred, downsizing, particularly on the sales side, is very much pharma's strategy du jour.

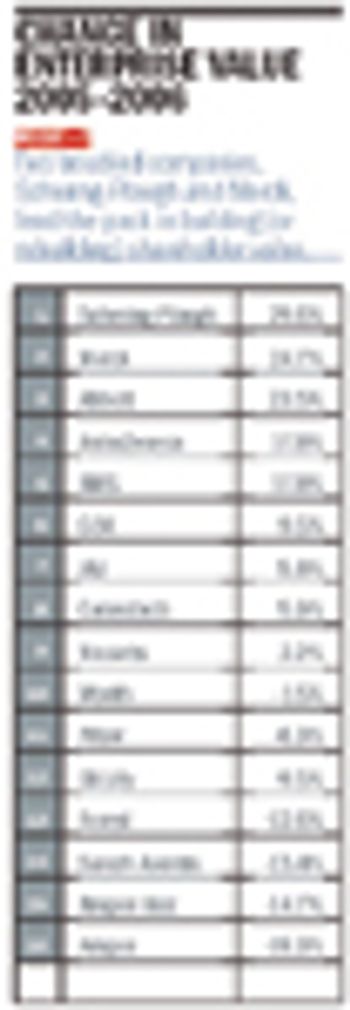

For the sixth year in a row, Pharm Exec invites Professor Bill Trombetta of St. Joseph’s University to analyze the pharma industry's financial performance with a battery of business metrics, old and new. The highlights: Genentech pulls ahead of its longtime rival, Amgen. Forest delivers another strong performance, despite dropping revenue. Schering-Plough is building enterprise value. Biogen Idec racks up a stellar profit margin. And Merck? Well, Merck is back, baby. And the winner is…

Many see Vioxx and Avandia as clear signs that the drug safety system has failed. As soon as reports of these drugs' adverse events began to flood the media, consumers-and Congress-demanded to know: "Why didn't we know sooner?"

Is the American Medical Association's (AMA) Prescribing Data Restriction Program (PDRP) the answer to physicians' privacy concerns, or will it just hamper the relationship between rep and doc? Observant LLC recently gauged reactions to the PDRP and doctors' expectancies of how this initiative affects physicians' practices and their relationships with pharmaceutical representatives. The findings suggest that the initiative may have paradoxical negative implications for physicians.

It's certainly not headline news that these are tough days for the pharmaceutical industry. More than $60 billion in revenue from blockbuster drugs will evaporate as these products go generic over the next five years, while the productivity of clinical development has hit a particularly rough patch. Even in the companies with relatively strong pipelines, many of the new treatments are biotech products acquired out of house. The expected authorization of biogenerics will squeeze profits only further.

There is probably not a senior executive on the planet who, at one time or another, hasn't raised an eyebrow or two to express exasperation over "people problems." But just try to run the modern business corporation without them. Forget the Internet chatter about the peopleless workplace. There’s no substitute for the contribution people make to the bottom line.

here's a solid case to be made for choosing A. The market for deals has been robust through the first half of 2007. A Cowen research report counted 10 public deals done by July 2007, compared with 14 for all of 2006. Another data source, Irving Levin Associates, cites 455 public and private healthcare deals in the first six months of 2007, a 12 percent decrease from the same period last year-but an 18 percent rise in deal value.

It's testimony to the high anxiety-and hectic activity-in the industry that the merger of German chemicals-to-pharmaceuticals firm Merck KGaA and Swiss biotech Serono elicited only faint fanfare. Both family-owned drugmakers boast an illustrious heritage, but their union garnered none of the pomp and circumstance befitting a marriage of European royalty.

New marketing agency helps pharma companies clean up their act

A new class of scales that can help capture drug effects-not necessarily disease impacts, as quality-of-life instruments currently do-will likely be needed to identify the meaning of the drug's benefits to patients